THE POLISH NATIONAL CHARACTER

This section covers exciting topics such as: #Polish mentality #Food #Are Poles alcoholics? #The importance of family #When are you an adult in Poland? #Poland’s ill fated destiny#East, West… neither #How about the genders #Are Polish girls cute? #What about the guys? #How do you talk to a Pole? #Poland’s place in the world #Hierarchy and responsibility #Trust #God, the Church and the Virgin Mary #Do Poles have sex? #Are Poles racist?

Polish mentality

A anti-woke and deeply subjective description of the Polish people. Remember that these descriptions are generalizations and may not apply to every individual. 😊

SALMONSENS ENCYCLOPEDIA, 2. EDITION 1925:

The Poles are known to be easy-moving in the mind and quick to perceive; their national feeling is strongly pronounced. The South Poles are more lively than the heavier North Poles, and due to the influence of the Germans, the inhabitants of the western part of the country are more developed than the people in the East. The highly conservative Mazowians around the Wislav River form the core of the Polish people, but when we talk about Poles in general, we tend to associate them with the idea of Krakovians, intelligent, lively and strongly-built people from Krakow.

Polish mentality

Poles are … very different in their attitudes to life. Attitudes are also changing relatively quickly. So it’s incredibly difficult to say “that’s how Polish people are”. But of course, there are some common denominators, as most Poles have seen the same films, have been exposed to the same books in school, and are told the same “truths” over and over again.

In the old days it was a little easier. There was state television and fairly standardised news reporting, so until 1997 there were a number of universal truths. It began to crumble when the television monopoly was broken. Today, it’s all fragmented, and while there is still a large proportion of the population that watches news broadcasts, the majority of news coverage and influences in general come from the internet and social media.

When you’ve lived in a place for many years, you start to perceive old truths as eternal and don’t always keep up with how society evolves. I’ve fallen into this trap several times myself. I’ve tried to shake my head, forget what I know and look at Poland in a completely fresh way. I’m excited to see how well it will work.

FOOD

Food is many things. Food can be something you consume to fulfil your body’s needs. Food can be rituals, it can be the memory of childhood. Food can also be the memory of hunger or the fear of hunger.

There is still a symbolic meaning to sharing food in Poland. Not long ago, I attended a lecture on Danish culture. During the ensuing discussion, one of the audience members highlighted the selfish behaviour of Danes – if you come to a Danish home, you won’t be invited for so much as a plate of soup, and here in Poland we share EVERYTHING.

Her comment made me think of Poland in the 1990s, when I simply lost my appetite and got an eating disorder because I was fed up with being force-fed every time I visited my girlfriend’s extended family.

I actually thought that the food-sharing culture was in retreat among the younger urban population. It may be, but it still exists. Especially in smaller towns, visits are associated with cakes (homemade!), but also something more solid.

As mentioned, the sharing culture can become a culture of compulsory eating. Often, you as a guest are expected to eat, and many will take offence if you don’t help yourself to the prepared dishes and praise the delicious food. So… EAT! – if you don’t want to offend your host. But wait until you’ve been urged. And even if you say “no thanks”, some will be convinced that you’re saying no out of politeness and will go to great lengths to convince you to “give it a try”.

Older people will still remember the period after WWII, when hunger was knocking on the door. Some people like to have stockpiles just in case something happens. And as the audience member in the session on Danish culture emphasised – it’s important to share. I’ve even seen stockpiling with younger people who have gone through difficult times. It’s nice to have a full fridge and some long-lasting cans in the cupboard. And then there was the time you got half a pig from the countryside that needed to be stored. You don’t do that anymore, but it’s in the collective memory. On the other hand, pickling is quite concrete. Many people have an allotment garden, and we all know that food tastes better if you’ve grown it yourself. And if you don’t grow your own garden, you can go mushroom hunting in the forest. These products are also poured into glass jars and stored for the rest of the year. Usually you have too much of it, so the jars are distributed to family and friends.

However, food storage is now facing an opposite trend. Supermarkets sell ultra-processed foods and many – especially younger generations – forget about food preparation and storage. It just needs to be quick and easy. And it can be even easier if you simply order your food from the local Little Frog (Żabka – Poland’s answer to 7/11), pizza man or shawarma bar, who will deliver your dinner in a plastic bag without you having to leave your apartment.

In contrast to many other countries in Western Europe, food is probably still more about feeling full. If you go to a restaurant, the food should be plentiful. This doesn’t mean that the food shouldn’t taste good, but it should be filling first and foremost. And even though it’s on the decline, there’s probably still a bit more reverence for food as something ritual, something you don’t just throw away.

ARE POLES ALCOHOLICS?

Poland is known for being in the vodka belt, and many people from Western Europe still have an image of Poles drinking themselves into a stupor every time they get a chance. And there’s no denying that vodka was a major comfort in the 1980s and 1990s, when the economy was in stagnation, food consisted of soup, cheap sausages, potatoes and cabbage, but vodka was relatively cheap. Camaraderie was fuelled by a vodka bottle, and if people weren’t drinking, it must be because they were trying to hide something.

However, that was a long time ago.

But even in the good old days, vodka drinking was something that only happened occasionally. Many Polish acquaintances shake their heads in disbelief when they realise how much beer and wine people consume in Western Europe on a daily basis. Only 1.6% of Poles drink every day, while the same figure is 7.5% for the Germans and 20.7% in Portugal. When it comes to the question of when Danish youth can drink at school parties, the mask often gets a little tight. Young people in Poland only drink in secret. But one thing most Poles are longing for is the ability to buy a hawker beer and sit in a park or public square and enjoy the good weather with friends. Legislation and the police are putting a stop to this in Poland.

Even at large social events, where unconsciousness has previously been the measure of a successful party, people seem to approach the bottle more calmly today than in the past. At the last Polish wedding I attended, there was still plenty of vodka left over after the party, while the hosts had to go out and get more wine, which has traditionally had more of a decorative function.

Things are changing though. Even though getting-dead-drunk-in-vodka is becoming a thing of the past, city centre pubs are trying to promote elaborate shots to boost the mood. And many people have started drinking a glass of wine with dinner or having a few beers in the evening. This daily consumption was definitely not frequent in the past.

But … all in all: Poland is in the average of pure alcohol per adult with 9.7 litres per year (and it’s not because there’s a lot of home brewing), but really the differences are not striking. Europeans like a drink.

THE IMPORTANCE OF FAMILY

The family is the basic social network in Poland. The law states that if you can’t take care of yourself, you must provide financial help to parents, grandparents, children, grandchildren, and even uncles, aunts, cousins. However, it’s rare that anyone goes to court. The awareness that the family helps each other is not up for discussion, and most people don’t realise that the law obliges the family to support each other. They just do it.

The background is a society that has not had welfare assistance, where unemployment benefits have been minimal and financial aid during studies have been scholarships for the most talented. Maybe the Catholic family tradition also has some significance. In any case – a Pole doesn’t trust his state to help if he has social problems, but most people trust their family to do so.

It also means that major expenses often become a joint effort – whether it’s a new bike for the teenager, a computer or an apartment, the whole family often comes together as a community. Family sentiment also means that you do what you can to leave something for your heirs, and it’s not like young people get a bag of money. Families will often argue over who needs Grandma’s apartment the most when she dies or moves in with one of the children – because it’s still not socially accepted to send your parents to a nursing home, even though the number of private and excellent nursing home places is increasing.

The exchange of money also leads to social control. When you’ve got a new bike or grandma’s flat, you somehow have incurred a debt and now have to pick up the tab for the other family members. The outcome can also be, that you listen a little more to the rest of the family and do not make big, sudden decisions on your own.

As mentioned, you help each other. Grandparents are therefore expected to take care of the grandchildren. There may be difficulties with nursery places, and even kindergartens, but it’s fortunate that women can retire at 60 – exactly the age when you can start to make a difference. Sometimes the elderly rebel, but it’s rare. In return, the elderly can look forward to living with one of their children when they reach the age where they can’t take care of themselves. It’s rare for the elderly to go to a nursing home, if only because the children will receive disapproving looks from their peers if it’s rumoured that they send their elderly parents out among strangers. The question is whether it’s not a system that’s about to fall. From large, solid herds of children, Polish women have stopped having babies, so if there are any descendants at all, they will usually only be a maximum of two. So there are fewer people to take care of the elderly.

Textbook for 8th grade: On the road to adulthood – Preparing for family life

WHEN ARE YOU AN ADULT IN POLAND?

Just like in most European countries, you can vote and get a driving licence when you turn 18. You can also buy alcohol, get into debt, get married and, if you have the money, move away from home.

But… few people have the money to move away from their parents. If you do, it’s because the family council has decided that you should have grandma’s flat, or if you’re studying in a city far away. Then parents will sometimes try to scrape together the money to rent an apartment near the university.

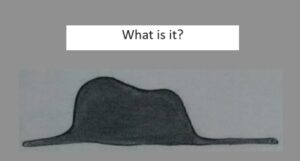

The “When are you an adult” test could easily be completed by anyone who has read The Little Prince

But … although young Poles often emphasise their individuality, you’re a child longer than you are in many other European countries. And here I realise that helicopter parenting and the infantilization of teenagers is on the rise almost everywhere. But it is increasingly common in Poland, where there is a general awareness that children need to be protected. Children’s books are generally very innocent, and any explicit sexual, physical and social content will make Polish parents want to cover their children’s eyes. As such, I also believe that many young Poles grow up with a slightly more “innocent” attitude to life than their counterparts in my home country.

Many parents also take great care of their children even after they’ve left home. It’s normal to do your laundry in your parents home and get a proper packed lunch when you leave. It can continue as a tradition to a very old age.

Of course, the tradition of the whole family helping out also increases social control. You know who to stick with, and even if an 18-year-old has retracted the money from the children’s saving account, it won’t be used for a gap year in India – at least not without parental blessing.

Polish young people leave home earlier than their peers in Italy and Spain (where they are on average 30 years old before leaving mum’s cooking), but 29 years on average in Poland is still a high age. At least if you compare it to 21.7 years in Denmark.

You could speculate whether the late departure is particularly Catholic-inspired, but I think most Polish youngsters actually dream of just getting away from their parents’ embrace. The problem is low wages, high housing prices and other issues that make it almost impossible for many young people to get away from their parents. But some do, and that means you can also find Polish teenagers aged 35 and 40 who still have a room at home.

POLAND’S ILL FATED DESTINY

Poland’s history of suffering goes back a long way and lies like a cloak of destiny over the Polish people. Poland is the bulwark against Russia, the bulwark against Muslims, the protector of Europe. Poland is the Jesus of nations – the nation that must suffer for Europe. And suffering is seen here more or less consciously as a natural part of life.

The Poles have been skilful at exporting that story, so skilful that it is common knowledge among people in Western Europe that Poland has suffered hard and deserves understanding.

In any warring nation, children are influenced by their parents’ experiences, and this may also be passed on to their grandchildren. People who have been exposed to traumatic experiences react in different ways to these experiences, but there are always elements of pain, grief, guilt and other emotions that may be hidden but still show up in one way or another.

Here, of course, Poland has been influenced for a few generations, perhaps most strongly from World War II, where everyone was exposed to the horrors of war, but also World War I, where Poles were cannon fodder for three warring empires. And then came a series of wars to establish the new Poland’s borders with its neighbours. The suffering and scale is huge, but then again a lot of countries and people suffered during the world wars.

However, I am not sure to what extent the suffering of the two world wars is directly related to the Polish history of suffering. The story is much older, and here it is questionable whether the suffering of the uprisings against Russian rule, which after all only affected a limited part of the population, can be included. Katyn – where 22,000 Polish reserve officers were killed – is often emphasised as an extermination of the Polish nation, but I find it hard to see that it had a greater impact on Polish society than the millions of other people who were killed.

The suffering is part of the literature and narrative of the Polish people – not just the messianic narrative, but in the story of people who live in miserable marriages but sacrifice themselves for the sake of family and nation. Suffering is beautiful and Poland stands alone!

Nor should we forget the popular narrative about France and England, who, in Polish opinion, betrayed Poland at the outbreak of World War 2. Instead of immediately coming to Poland’s aid, France waited for Germany to overrun the country and install a French puppet government. England, on the other hand, waited and hoped for a negotiated solution. While these are not the official narratives of World War II, they are heard everywhere, often harbouring a deep contempt for France and a certainty that Poland stands alone.

Far be it for me to deny that Poland has indeed had a tough period in the 20th century, although … many people in many countries suffered terribly. But then again… Poland was the nation that was hit the hardest in terms of population.

Of the history from before World War I, the Polish suffering is actually quite ordinary. Poland-Lithuania was a great power in the 16th century. It was aggressive, expanding and oppressive. In the East, Poland created colonies where peasants were oppressed in a way that is incomparable to the situation in Western Europe. The situation of the serf Polish peasants can best be compared to that of the African slaves in America. At the same time, Poland missed out on the emerging transformation of the economy in Western Europe, where production became increasingly specialised. Meanwhile, Poland produced and exported agricultural products that they could only monetise because the peasants were seen as objects or animals that only needed to be fed enough to survive.

Poland’s decentralised political system meant it could not maintain its position as a European superpower, and in a series of religious and independence wars from 1570 to 1795 involving Russians (Orthodox Christians), Swedes (Protestants), Turks (Muslims), Ukrainians and others, Poland gradually lost its power and eventually disappeared from the world map. It’s a sad tale, but it is, after all, a tale that has been repeated over and over again in the history of the world. During roughly the same period, culminating in 1864, Denmark finally lost its great power status and became a petty state.

As a resurgent nation, however, Poland may be more in need of a romantic narrative, and there is no indication that Poles will de-emphasise their suffering in the years to come. Although … perhaps a new group of young people is emerging who see Western Europe as their homeland and who don’t attach so much importance to the myths of suffering Poland. Only time will tell.

EAST, WEST … NEITHER

The first pressing question is what is East and what is West?

If you belong to the West, people from the East are less civilized… less developed, more primitive than the inhabitants of the West. They are also more religious and place more emphasis on tradition. They don’t like new things and are sceptical of big cities and foreign countries, which tend to deprave people.

And if people from the West are to define themselves, they are open to the Western world, adaptable, like travelling abroad, respect people’s right to believe in God, but don’t necessarily need to go to church themselves. They like new things and accept diversity.

And if you come from the East, you will probably agree that they emphasize tradition, religion and Polishness, while we all know that people become depraved, greedy and immoral when they leave their native land.

It’s popular to refer to the old zones when talking East and West. Has the area been German, Russian or Austrian? However, the inhabitants of Poland have become so mixed that it’s not a very convincing argument. People in the West – i.e. Wroclaw and Szczecin, are predominantly people who were displaced from the eastern areas that are now part of Ukraine. It may have some significance, especially when we are talking about cities that were not destroyed during WWII – Krakow and Poznan, for example. However, in my opinion, the attitudes of East and West have more to do with population density.

Actually, much of the East-West issue could be translated as sparsely populated parts of Poland. People also talk about Poland A and B or sometimes Poland A, B and C to refer to the old Russian, German and Austrian territories

However, you’ll also find many who emphasise Poland’s uniqueness. Poland is neither East nor West, they claim. Poland is a middle ground, a mixed society that has absorbed elements from both corners of the world. It’s been told so many times and for so long that most people now realise that Poland is not in Eastern Europe, but in Central Europe.

But no matter how you define it, Poland is divided in terms of attitudes to life; and if you’re a Western European walking around Warsaw, Gdansk, Wroclaw or Krakow – you won’t really feel much difference between these cities and other major Western European cities. On the other hand, you’ll experience a cultural journey if you go to Lublin or Bialystok.

To return to East and West, the difference is perhaps much simpler than all the mind games I’ve been doing for the last 8 paragraphs. Perhaps people are just more conservative in the countryside, in the sense that they don’t like ambiguity and doubt in their world-view. Things should be organised in a certain way. The West, on the other hand, may be those people who are influenced by a world-view that questions many of the things they encounter as they walk through the world.

GENDER ROLES

As with so many things, it’s not that easy in Poland. Some elderly gentlemen will still take a lady’s hand and place a hint of a kiss on it, others will lick the hand a little, especially if it’s a particularly attractive woman. It’s an old custom meant to show chivalrous respect for the weaker sex. It’s now rare in cities, but not so many years ago it was quite common. I don’t know many women who think it’s cool.

However, it’s not clear-cut. Traditionally, Polish women expect men to hold the door for her, wait to enter a lift, hold the chair at the restaurant and a lot of other gallant things. And even though it’s on the decline, there are actually still many women who will consider you to lack manners if you enter a lift without first signalling that women have the right of way.

Traditional gender roles still prevail in many places. In the family, it is usually the woman who does the housework, or at least the majority of it. And when it comes to looking after the grandchildren, it’s the grandmothers who are called upon, less often the grandfathers. Here again, we are in the East-West divide, because while one part of the population sees this as a natural state of affairs, the women in the other part of Poland give a middle finger to such attitudes – and the men have also realised that there is no point in clinging to traditional gender role concepts. Young and middle-aged men are increasingly identifying as soft men.

Many women are frustrated with the expectations of their place in society and define themselves as feminists. Now feminism is many things, I once thought it was about equal opportunities for everyone, regardless of gender. However, many Polish feminists emphasise their femininity and expect special recognition of their gender. As such, it is not clear what it actually means when people talk about feminism, just as there is no clear position on what the roles of women and men should be in Poland.

On the other hand, many women don’t give it much thought. They get a solid education in fields where they expect their labour to be valued. When you look at doctors, lawyers and university lecturers, the majority are women, and many of them are neither feminists nor the opposite. They just need a career. It’s a similar trend seen in many other European countries.

And there are plenty of opportunities to develop your career. Each woman gives birth to an average of 1.26 children, so it’s not the childbearing that’s getting in the way. And perhaps the desire for a career is actually a significant part of the low fertility rate. And especially in cities, many people don’t seem to be in a hurry to start a family. The average age of marriage is 29, many don’t bother – either they live together without being married or they just choose to live alone. It also means that career women don’t just let themselves be moulded by a prince who comes into their lives after they’ve graduated and landed a good job.

Finally, we can look at gender placement in relation to gender identification. Gender relativism is a topic that can get many traditional-minded citizens up in arms, and many fear that schools and kindergartens are raising a bunch of blue-pink hermaphrodites who mate like earthworms. This is far from the case. Polish schools are relatively conservative, but the very idea that you’re not 100% male or 100% female can lead some people to anxiety attacks.

For now, though, there’s nothing to worry about. The vast majority of Poles (together with Spaniards and Italians) identify as real men or real women, unlike in Scandinavia, UK and Germany where most people feel they have both masculine and feminine traits.

ARE POLISH GIRLS CUTE?

The traditional and inevitable question when I came to Poland in the 1990s was, “what do you think of Polish girls”? At first I tried to politely reply that they were very nice, but gradually the question was repeated so often that I felt like vomiting when I heard it. It seemed as if Polishness had to be confirmed by me, as a foreigner, praising Polish women.

Incidentally, the 1990s was when many Polish girls saw a guy from Western Europe or America as a ticket out of economic misery. Or maybe it wasn’t just that – the Western European men had money to party and were happier than the Polish men, who were usually brooding about their future prospects. Whatever the reasons, however, there is no doubt that there was a period in Poland’s history when being from the West had enormous sex appeal.

It’s over! That is, it’s not quite, because Polish women are exploratory and many will find a foreign man exciting. But in that respect I don’t really think they are any different from women elsewhere in the world. The unknown is always more exciting than the familiar.

So now I will – finally – return to the headline; are Polish girls cute? The answer is: “Yes”. As I hinted in the previous paragraph, I don’t think any Western European guy should expect to find a submissive housewife in Poland, but… if you’re from Northern Europe, Polish women clearly place more emphasis on being a woman, they dress more femininely, and they’re far better at flirting and playing with the spark between the sexes in a way that might not be entirely welcome in Scandinavia. They may not be quite as skilful as in France or Spain, but they’re not quite as hopeless as in Scandinavia either.

And then I’ll come back to the “sweet”, which I don’t see as exclusively positive. Polish women smile a lot and move in a feminine way, but … I miss the animal aggressiveness that is sometimes seen among Ukrainian and Eastern European women. There may be a lack of challenge to prove something. It can all get a little too “sweet”. It’s provocative, of course, it’s meant as a provocation, but it’s also an answer to the question I’ve received so many times that I’ve had to think about it.

…… WHAT ABOUT THE GUYS?

This is a subject I know a little less about, but from what I understand, there is quite a difference between Polish guys. Many will be very chivalrous, invite their lady of the heart out and hold the chair for her, buy her flowers and go out of their way to convince her that she is the most unique thing God ever designed.

Conversely, I’ve also heard stories of Polish men who, after a few beers and a dance, expect her to walk home with him, and when you ask him to buy a packet of condoms, he waves his hand and says, that then we can forget the whole thing.

If a Polish guy is in a relationship, he will often be a little more serious about his “intentions” than a guy from Northern Europe will necessarily be. But then again… life is a little more serious in Poland than it is in the West.

HOW DO YOU TALK TO A POLE?

It might not always be easy to make that first contact. In some neighbourhoods, people don’t look at each other, but in most apartment blocks, people do say “hello” when passing each other.

Poles are keen to be seen as open and friendly, and most people are convinced that this is how Poles are. However, it’s not quite that easy. You can connect with others when you go out in big cities, but preferably when the bar is packed. Otherwise, you bring your friends with you and don’t talk to people from other groups. There’s no immediate “amigo” greeting to people you don’t already know.

It’s a fact that Poles are sceptical of strangers. If a stranger approaches you, you will often expect that they want something from you. Again, things have changed drastically from the 1990s, when people went out of their way not to make eye contact with each other. Trust is still lacking, but it’s building and people are connecting with each other.

In general, you should say “hello” to people you meet more than once. Then trust will be built. As in the rest of Europe, eye contact and smiling are also great ways to build trust.

The personal space is similar to that in Northern Europe; you keep about an arm’s length away from your conversation partner. Get too close (remember that, if you happen to be Spanish) and it gets uncomfortable (unless you’re dancing). You may find a bit of gesticulation, but it’s nothing like Southern Europe.

Imitating the hand kiss of older Poles is generally not recommended. Instead, a medium handshake for men, a light handshake for women and a slight head bow will send a signal of equality that will be appreciated by many. At least in more formal settings and when meeting someone for the first time.

Embraces and kisses on the cheek (one or two kisses) are common greetings among young people in social settings, both for hello and goodbye.

POLAND’S PLACE IN THE WORLD

No Pole doubts that Poland has been a European superpower. Many countries have once been great powers, but most of them have accepted the fact, that this is something of the past. In Poland the country’s former size is repeated again and again, and the gradual dismemberment of Polish territory is seen as a gross historical injustice.

At the same time, there is an awareness that Poland’s economic situation has left the country far behind Western Europe. This is slowly changing, but there is still a sense of being a less affluent relative – and sometimes Poles feel exploited and abused as a supplier of cheap labour.

Regardless of the lost territory and economic situation, most Poles realise that Poland is a great nation. The 38 million Poles in Poland are often combined with the grandchildren of emigrated Poles, bringing the total to around 20 million Poles in exile. If you then (as some politicians have tried to do) combine this with the Poles killed during WWII, then Poland is suddenly almost as big as Germany. Perhaps it’s not so much about tangibles, but more about the feeling of greatness.

This has perhaps contributed to a certain amount of uncertainty when dealing with the rest of the world. Poland has a special relationship with Russia, Germany, Ukraine, Hungary and the USA, and a few other countries, but all relationships are very tense. Big things help build confidence. A forest of exclusive high-rise buildings in the centre of Warsaw shows that Poland is a new version of Manhattan. With the largest share of Europe’s gross domestic product spent on the military, Poland creates an army of enormous size. A central giant airport is planned, modern miniature nuclear power plants are planned, and canals have been dug so that you can sail into Poland’s canal network without coming into close contact with Russian territorial waters. Much of it is planned politically and the aim is to create a new sense of national self esteem, but it’s also something many Poles feel Poland deserves. It’s something Poland needs to show the rest of the world what Poland is all about.

Things are actually going really well in Poland, people are generally happy with their lives and economy, although of course you always want more. But there is a kind of inferiority compared to Western Europe, and this inferiority creates a need to puff up. This can be seen in the introduction to Salmonsen’s Conversational Encyclopaedia, where Germany, as the most natural thing in the world, is listed as “more developed”. And that awareness exists among many in Poland: East = underdeveloped, West = developed – and this also applies within Poland. It also creates a certain amount of hatred towards Germany, because is it really fair that this is the case? In addition to lack of war reparations, Germany’s crime is that they are richer than Poland. And, of course, that they were involved in the partition of Poland between 1772 and 1918.

Poland’s other major enemy is Russia, which dominated or ruled Poland from the early 1700s. It’s a crime, because it should have been Poland who won that match and came to dominate Russia. It was a period characterised by great brutality and attempts to eradicate the Polish nation. Today, the story of Russia’s crimes is repeated endlessly – in schools, literature, films, museums and stories, and it’s all repeated one more time on social media. Russia is evil, and the recent war in Ukraine has proved, that Poland is right.

Ukraine is also a special relationship. On the one hand, the country is of course a neighbouring nation, but Poland ruled large areas of Ukraine until the outbreak of World War II. Plenty of Ukrainians have a Polish grandfather or mother, and plenty of Poles are descended from areas of Ukraine, and their ancestors may not be clearly defined as Ukrainian, Polish or anything else. The close relationship has also left scratches in the love. Although it is not widely recognised in Poland, I would venture to say that until 1648, much of Ukraine was a Polish colony. The Khmelnytsky uprising of 1648-1657 was intended to create an independent Ukrainian state, but ended up tying Ukraine to Russia. Khmelnytski himself is perceived in Poland today as the personified evil, while in Ukraine he is a national hero. Under Austrian rule in the 1800s, the Polish people sought and gained a degree of autonomy in Austrian Poland, while fighting Ukrainian efforts to gain the same rights. And after the restoration of Poland in 1918, there were uprisings, murders on Poles, repression from Poland, relocations and many other ugly things, with both Ukrainians and Poles bearing some of the blame for death and suffering. Some of the hatred towards the Ukrainians still exists in Poland, even though the war has partly united the country against a common enemy – Russia. However, opposition has developed against the support for Ukraine and Ukrainian refugees. It’s evident when you talk to people in smaller towns, it’s seen in graffiti and on social media.

Conversely, Ukraine is an old Polish territory and a not insignificant group would like to re-establish Poland’s old power. Ukrainian accession to the EU could be one way to do this.

Hungary is seen as an old ally, and there is a tale of eternal brotherhood between Poles and Ukrainians – “Polak, Węgier, dwa bratanki, i do szabli, i do szklanki” – Pole and Hungarian — two brothers, good for saber and for glass; this is said in both Polish and Hungarian.

Deep down in the hearts of many Poles, the US is probably the only real ally. The country is that far away that it doesn’t interfere in day-to-day affairs, and trade is limited for the same reason. Polish freedom hero Kosciuszko fought in the American Revolutionary War, many Poles have emigrated to the US, and Chicago is sometimes referred to as the second largest Polish city. The US had decisive influence on Poland’s re-establishment as an independent state after World War I, and American nuclear missiles are seen as a guarantee of future Polish independence.

Especially nationalistic Poles are likely to view most of the world with some scepticism, especially countries that are close by. Many see international trade as a zero-sum game, where a benefit to one country is a corresponding loss in another country. When things are going well in Poland, they must be going badly in other countries, so it’s natural for them to be envious of Poland – at least that’s the reasoning of former Prime Minister Kaczynski, but he’s certainly not alone in his view.

HIERARCHY AND RESPONSIBILITY

Poland is a society that is characterised by clear lines of command at all levels, very much like a lot of other societies, but very much in contrast to my home country (Denmark). In most families, you know who is responsible for what, and many children (but of course not all) still respect mum and dad, both as children, but also as teenagers and young adults.

The hierarchy also works in society, where you will rarely find a flat organisational structure. There are also a lot of symbols associated with power and leadership, and sometimes I get the impression that senior managers are a little too keen for everyone to see that they are leaders.

This structure also means that few are willing to take responsibility for making a decision. You call first and ask the supervisor or get a signature so that you’ve got your arse covered. It’s always good to have someone to blame.

Every mayor of a large city has 3-4 deputy mayors that he has personally selected, and of course they all have their assistants, who together form the mayor’s “court”. The same structure is seen in most government organisations and state-controlled companies, where the top manager appoints assistants because they have a personal trust in them, and they then appoint their own assistants. This often results in a web where people are employed in senior positions because they can be “trusted”. And in larger public organisations, such as the Social Insurance Institution, this web can become extreme.

The boss is often the God you’re afraid of. It also means that young specialists rarely get the challenges they dream of, because difficult tasks and involvement are rewards handed out within a web of contacts, and many times it seems like you’re a little afraid that the younger and untested ones might challenge your own power.

Alongside this is a culture of favours and buddies that can sometimes seem a little mafia-like. For many, a good job is something you should be recommended to, and doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with qualifications. So if you want to get ahead in the world, you’ll often prioritise networking over upgrading your skills. It is, of course, a structure that is under pressure from many private – and particularly international – companies, but much of Polish business is heavily influenced and partially owned by the state, and here traditional structures often continue in the same way as always. Often, political parties and church organisations are also on the periphery of these ‘friend structures’ and are therefore also influenced from the outside.

Responsibility in Poland is individual – at least in the common perception. It’s very difficult to make an organisation responsible for anything. You want “the guilty person” and the guilty person is guilty, even if it’s an unavoidable mistake. No one can go through a working life without making mistakes, but woe betide the one who gets caught.

One example is a retail chain that recently dismissed an employee for overlooking the theft of 12 cartons of milk in a shopping basket covered with a bag. The store went to both city and high court to uphold the dismissal, but lost both.

Another example is hospitals, where the individual doctor is held accountable, hardly ever the hospital or healthcare system as a whole.

The individualisation of responsibility is also seen in the way people communicate with public authorities. You don’t write a letter to the Ministry of Education, the municipality or the tax office, but to the Minister of Education, the mayor or the director of the tax office.

But the whole system seems threatened. On the one hand, the courts sometimes seem to start imposing liability on organisations, and on the other hand, the quiet girls are pouring into the workplace, taking up positions as doctors, lawyers and researchers at universities. It’s often women who are more likely to come forward because of skill, and they often seem to be less engaged in the rituals of friendship. Both of these things I believe will create a change in the future.

TRUST

When I talk to business owners in Poland, one of the things I often hear is the problem of “trust”. If we look at an annually repeated survey from the Polish polling institute CBOS, the results have remained largely unchanged over the last 20 years. 77% of people believe that you should be extremely careful in your relationships with other people, 23% believe that you can generally trust other people. This result is better than Portugal and more less like France and Italy, but miles from Germany, Spain, UK and the Scandinavian countries.

I often think of a conversation I overheard some years ago in a marketplace where two citizens were talking. As one explained to the other: “PiS (then ruling party) also steals, but at least they share what they steal with the people”.

And that’s probably a very good summary of the general attitude towards politicians, parliament and government. Scepticism towards the political system is (perhaps not without reason) very high, and it may in fact reflect society’s general attitude towards the unknown. You agree on a price before the contractor starts and you find it natural that the telecoms company tries to cheat on the bill.

Stamps and extremely long contracts are part of the legacy of the past, and although the stamp is becoming an anachronism, it’s still part of the mentality. Often you have to sign 5-6 different places on a larger document, and it’s made worse by the fact that many require signatures to be “legible” – in other words, in block letters.

No one reads the long contracts, and if anyone actually sits down and reads the long contracts, the other party stands there tripping alongside. Furthermore, few people understand the contracts, which are filled with strange and intricate clauses. A lawyer working in the administration at a large bank told me that she herself doesn’t understand the bank’s contracts.

New legislation protects consumers and many clauses are declared void if they are in standard contracts, but not everyone knows this and they are still being abused. A standard remark is a shocked facial expression and the question: “Haven’t you read what you signed?” This is not something that promotes general trust in society.

Rules are good, there are detailed rules for a lot of things, which means you don’t have to worry about making mistakes. The world can then be divided into what “I/we are committed to” and what “I/we are not committed to”. This in turn means that things are often not done based on reasonableness, but on learnt norms about how to react to a given situation.

INDIVIDUALISM OR COLLECTIVISM

It’s difficult to define clearly, because Poles are in many ways collective – in the family and in the church. On the other hand, they are far behind in terms of associations, perhaps because people don’t trust each other, private companies or authorities. You have to look far and wide for an association that represents your interests – be it sports, consumer activism, pro or anti-nuclear, or for that matter trade unions (to be clear, there are no strong trade unions in Poland, and the few weak ones that do exist are more like political pressure groups). Instead of forming a sports club, people spend a fortune on private fitness.

In general, people believe it’s best to deal with their problems themselves, and if they can’t, it’s usually the system’s fault. The self-image of the Pole as a person who opposes authority is cultivated, and this narrative is probably rooted in Solidarity (1980s), the Warsaw Uprising (1944) and several uprisings against the Russians in the 19th century. The story of individuality also goes back to the story of the Polish nobleman, where everyone was equal to any other nobleman (that’s a lie, but that’s how the story goes). Many people cultivate the ideology and try to make themselves as special as possible, but in reality, the vast majority of Poles are herd animals who don’t have the energy for too much individuality. You have to have a job and a home, and while there may be glimpses of individuality in some periods of your life, the vast majority of your life is centred around the rat race.

However, it is not possible to define Poland unambiguously. Many people don’t believe the state does anything for its citizens, and there is widespread tax denial, where people simply define tax as theft.

GOD, THE CHURCH AND THE VIRGIN MARY

God, the church and the Virgin Mary are important elements of Polish self-understanding, but perhaps more so in small towns. Here, as mentioned earlier, tradition is important, but there is also a much more intense social control – it is simply inappropriate not to go to church, and the priest’s sermon is often the basis for conversation about the world. In addition, the church often serves as the place where important information about the local community is exchanged.

If you ask churchgoers if they are religious, they will claim with dismay that they go to church, so of course they are. But I’m not so sure how deep it goes with contemplating the Lord and eternal life.

Tradition, on the other hand, is very important and the Catholic Church in Poland is very national. Walk into a church and it will be filled with nationalistic symbols that can seem just as important as Jesus.

Former Polish Prime Minister Szydło (right) with her Chief of Cabinet has a sense of style and fashion when visiting the Vatican!

The church is undoubtedly a place where people unite, but many also turn away from the church. The recent focus on clergy sexual abuse of minors has raised many eyebrows. The church and the nationalist wing of Polish politics have also become so entangled that many are turning away from the church for political reasons. One of these reasons is abortion and contraception, where the church has very strong positions, but it is also a general attitude where many priests clearly express their party political preferences.

However, religion doesn’t seem to have much of an impact on everyday life, and the role of the church has clearly been reduced over the last 20-30 years. But there is still a huge respect for clergy and other church representatives, who wield enormous influence as counsellors and opinion leaders at all levels of society.

DO POLES HAVE SEX?

Maybe… but not so much if you look at birth statistics. Each woman gives birth to an average of 1.26 children (2022). With an EU average of 1.53 children (2021), it’s a figure that predicts that in a few years there won’t be so many Poles left. This is despite the systematic improvement of child benefits in recent years, which today amount to 800 zlotys per child per month.

Among the reasons cited are poor childcare options, but the lack of prenatal screening and abortion may also play a role, as many women are simply afraid of being forced to give birth to a child with serious illnesses. And then there’s the career. A child gives a break in working life, and even though the financial situation today is better than it was a few years ago, people are not so wealthy that women can reduce their income. Plus, it’s nice to enjoy a little luxury when you’re finally in a situation where you can.

But apart from that, Poles are part of the general European trend – people are having less and less sex. The wildest erotic animals are active once a week, and only 15% reach that kind of wild activity level. 34% have sex a few times a month. The rest rarely or never. This is a significant drop compared to a few years ago, and young people agree that sex is boring, at least in committed relationships. All evidence suggests that higher education means less sex.

It may seem strange, because there has never been talked so much about sex before, and sex seems to be available in all forms if you just want to open your computer and write a short, exciting text about your desires. In big cities, gay people showing their sexuality openly are a sign that seats are in disrepair, and they compete with cyclists and vegetarians, who by some traditionalists are indistinguishable from gays and child molesters. In the old days, the church could (maybe) put a damper on people’s sexual behaviour, but today very few people seem to take the church’s moral teachings seriously.

As with so many things, nothing here is clear-cut. There are trends pulling in all directions, and the answer might actually be that Poles are becoming Europeans.

ARE POLES RACIST?

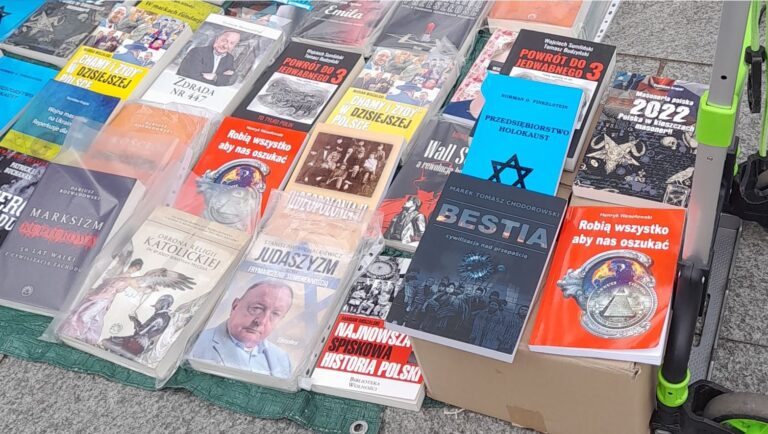

The short answer is – yes! Antisemitism in interwar Poland was at least as strong as in Nazi Germany, and Poland has never undergone any mental cleansing after World War II, except that it has provided a comfortable opportunity to classify Germans as barbarians. Poles discriminated against Jews before WWII, And during World War II, many Poles were involved in the persecution of Jews. Even the time after World War II saw pogroms against Jews. In the 1960s, Jews were scapegoated for political unrest and most of the surviving Polish Jews were forced to emigrate. And even in this Jew-free Poland, many will remember the story of the evil Jews, Jews are regularly discussed and many are of the opinion that Jews are hiding as Poles in order to harm Poland. There is also an extensive contemporary Polish literature on the Jews’ quest for world domination, and you’ll have no trouble finding films on the same theme on YouTube.

A collection of books is sold at a demonstration against Covid-19 vaccinations. The books are about Jews, and the titles include: They’ll do anything to deceive us, The Holocaust, Judaism, Betrayal No. 447, and much, much more, where the titles may not be that telling, but the content is deeply unpleasant.

The above is perhaps the evil version. Most Poles are nice and friendly people who may have their inherited biases to a greater or lesser extent. But … there is plenty of resistance to foreigners, also in other Western European countries, and the question is whether it is worse in Poland.

The official Polish historiography does a great job of presenting Poles as tolerant people who welcome strangers with open arms. “Polish tolerance” is a historical term that most people misunderstand, but this tolerance only refers to a brief period after 1573 when there was religious freedom for the nobility – not to Poland embracing foreigners in general.

An anti-immigrant election poster. “They murder and rape women and children” – the text reads.

Such was the desire to hide the participation of Poles in the extermination of Jews that in 2018, the government of the day introduced a law that sent people to jail for accusing Poland or the Polish people of complicity in the Holocaust. The law was later changed after pressure from the US and Israel, but had it not been, I would have risked a prison sentence for the previous paragraph.

However, many people are also proud of the Jewish cultural influence, many practise Jewish culture and some Jews have even started to return to Poland, some of them opening restaurants and cultural centres. And the hatred of Jews today is slowly disappearing, even if you don’t just erase something that has been whispered about in families for generations.

On the other hand, the hatred of Jews seems to have been replaced by a dislike of Muslims, and also I wouldn’t want to be black in Poland today. Many Poles have never been abroad, and if you see a person with “foreign” skin colour in a small town, people turn around to study the phenomenon.

With increased prosperity comes increased self-esteem among the Polish population, and foreign workers are increasingly being looked down upon. I have never personally experienced anything like that, but I also came to Poland from a Western country at a time when Poland was in a very bad economic situation. This meant that to some extent I was perceived as a representative of a ‘higher’ culture, and almost everyone found it difficult to understand why I had chosen to settle in Poland. Today the situation is different, but as a Western European I am still treated with kindness, especially since I am not German.

However, from being an ethnically pure society, Poland has received a large number of immigrants in recent years. The largest group here are Ukrainians, who came to Poland long before the last war in 2022, but there are also people from Asia and South America, and in general they have no problems finding jobs.

The past has been bad between Ukraine and Poland, and it is remembered, but it has been somewhat erased now with the common enemy in Russia. Some resistance against Ukrainians is starting to emerge, but it helps that it’s predominantly women and children, with few Ukrainian men travelling away. The women are given soft jobs in the care sector and appear far less threatening than if you had seen large groups of Ukrainian men.

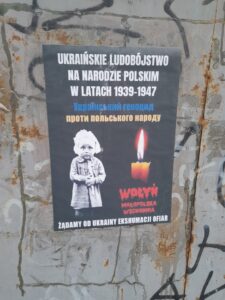

Ukrainian genocide of the Polish people in the years 1939-1947. Wołyń. We demand exhumation of the victims.

But even here, hostilities are slowly emerging, especially in smaller towns, with comments on internet forums and graffiti blaming Ukrainians for higher rents and for taking good Polish jobs. However, both language and culture are so close that Ukrainians will quickly integrate into Polish society.

Please send an email to m@hardenfelt.pl if you would like a English-speaking tour guide to show you the most important places in Warsaw.