The history of Gdansk

Gdansk is one of the oldest towns in Poland, and is mentioned for the first time in a document from the year 997 AD, which is considered to be the year where the town was founded. Gdansk thus celebrated its 1,000th birthday in 1997. Some settlements, though, had been at this place much earlier. Gdansk lies at the mouth of the Vistula River, and as from the 10th century, the town functions as a centre for the shipping of products produced along the river. Pomerania, where Gdansk is situated, is also a centre of interest for an east-going German expansion and north-going Polish expansion, which significantly influences the town’s character, being a mixture of several cultures. For several centuries the town is an independent principality, before it is incorporated into Poland in the 13th century.

The water front in the Old Town in Gdansk around 1900 AD

In the front we see the crane which since the middle ages helped loading and unloading the ships alongside the quay

In 1236 AD, Gdansk for the first time obtains its municipal charter, and as from 1260 AD the town is granted a papal patent, permitting it to hold a yearly market. Three years later a municipal charter under the law of Lubeck is granted, and after this the city quickly becomes a member of the Hanseatic League. As part of a political confrontation between Poland and the Germans it is incorporated into Poland but maintains its extensive autonomy, which is defended for the next 300 years. One of the important privileges is the right to coin money. Thus, Gdansk has certain independency from the central power for the entire period, and in 1569 AD the town e.g. refuses to take part in the new legislative union between Poland and Lithuania. After having been besieged for a while the town accepts the new political realities though.

The well-developed port gives Poland access to the European markets and causes prosperity in the trade with agricultural products. Gdansk has a local trade policy and should neither be considered Prussian nor Polish; the main objective is its status as a commercial town. The official language in Sopot and Gdansk is however German all the way until 1945, where the German population is expelled and substituted with refugees from other Polish areas. It should though be made clear that throughout its entire existence a Polish population has lived in Gdansk, and also that almost all Polish towns in medieval times were Germanised and based their legal system on German law.

The 13th century is a time of prosperity. The trade with other Hanseatic towns increases substantially, and the 14th century gives even more growth, especially when it comes to the amount of exported grain. At the same time, the trade with Dutch merchants is increased at the expense of other Hanseatic league members. A large number of foreign buyers settle in Gdansk, where they benefit from the regulations forbidding Polish merchants to travel abroad.

The 14th century is also characterized by the fight between Protestants and Catholics. Several charters confirm religious tolerance; the town also gives asylum to refugees from other countries.

The town becomes a power centre where people from all over Poland meet up. Gdansk is without competition Poland’s largest town; in 1600 AD it houses 50,000 citizens, compared with 10,000 in the Capital, Warszawa, and 17,000 in Krakow.

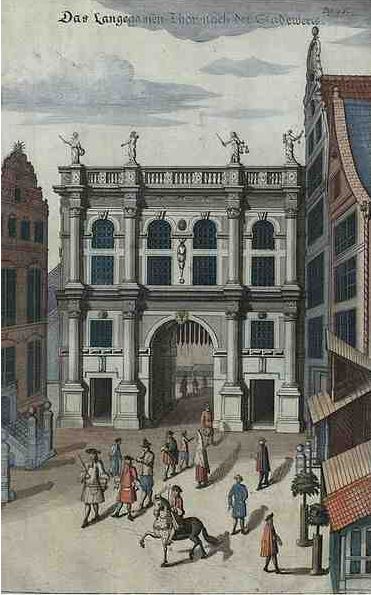

The Golden Gate in Gdansk 1687 AD – almost as it looks today

The town experiences yet another prosperity period in the 16th century, when the population reaches 77,000 citizens, and as regards riches and architectonic magnificence Gdansk can compete with any other town in the Baltic region. 1618 AD is the culmination point, when the amount of exported grain reaches a level 25 times higher than the level of 1491.

The Battle of Oliwa – 1627 AD

The Northern Wars leave a profound trace in Poland, especially from 1648. In 1656 thirty Dutch and ten Danish vessels break a Swedish blockade. The Peace of Oliwa in 1660 puts a stop to the Swedish deluge (potop), but the grain trade is already hampered by military operations and a period of recession begins.

In 1771, the neighbouring countries each take a lump of Poland. Prussia takes everything around Gdansk, thus isolating the town from central Poland. Consequently, the town loses a substantial part of its reason for existence. When the neighbouring states repeat the feast in 1793, Gdansk is incorporated into Prussia.

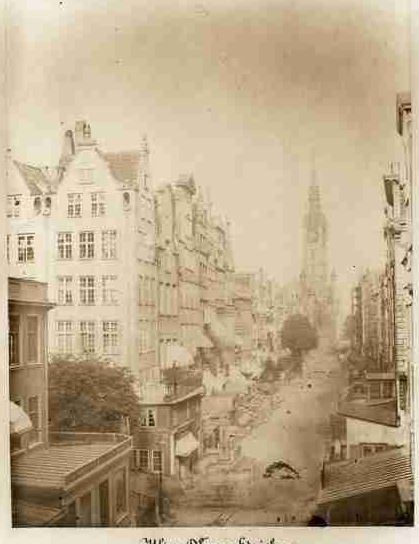

Ulica Dluga when Napoleon entered the city in 1807. The large terraces in front of the houses are clearly visible in this painting. The terraces were a typical part of Gdansk architecture, but were removed from Dluga Street in 1868 to improve traffic conditions.

As a consequence of the Napoleonic Wars, Gdansk becomes a partly autonomous free city for the period from 1807 to1814. In the beginning, the town manages brilliantly as a supplier of goods to the demanding war industry, but after numerous sieges and destructions, part of the town is destroyed. From 1814, Gdansk is under Prussian rule again, but the actual idea of a free city emphasizes the special character of the town, and the concept is also reintroduced at a later stage in time.

Sopot

Sopot has existed as a fishing hamlet since 1200 AD, but after coming under Prussian rule, the town starts to develop into a well-to-do area, where rich town-dwellers can relax during the summer. In the course of the 17th century, more public baths and parks are built, as well as the first pier. From 1870, a rail connection to Sopot is introduced, which helps develop the town as a tourist area. A number of hotels are built in what is described as the Riviera of the North.

From 1850 and in the decades to come, the infrastructure in Gdansk is developed substantially, new rail services are introduced together with a gas supply, water pipes, sewerage and horse-drawn trams. 10 years before the outbreak of WWI – in 1904 – the Technological University in Gdansk is founded.

Dluga Street 1855 – the oldest known photograph of Gdansk

After WWI, Poland re-emerges after having been under German, Austrian and Russian rule for around 150 years. The borders of the newly established state are not clearly defined from the beginning, and the borders are also a hot topic within Poland itself; a Great Poland encompassing several ethnic groups versus a national state with Poles and less ethnic minorities. Gdansk is mainly oriented towards Germany, and after WWI, only around 15% of the inhabitants are ethnically Poles. The Treaty of Versailles dusts off the concept of a free city, and in 1920 Gdansk gains the status of free City under the protection of Poland and the League of Nations.

Sopot comes within the jurisdiction of Gdansk and with the opening of the elegant Grand Hotel and the expansion of the pier tourism undergoes further development.

Even though the Treaty of Versailles guarantees Poland access to the port in Gdansk, it is politically unacceptable for Poland not to have a national cargo port. Gdynia has for several hundred years existed as a small fishing hamlet, though by 1920 it has developed into a village. In 1921, Gdynia houses 1281 inhabitants. However, the position is perfect for an international port, and leading political powers with the capital make an effort to build a modern harbour and create a commercial town at this place. They succeed and until 1939 the population is increased up to 127,000 inhabitants. Here we have the biggest cumulated investment in interwar Poland, mainly carried out with the help of private and foreign capital.

In 1933, the Nazis win the election in Gdansk and consequently establish close cooperation with the Nazi regime in Germany. German claims for a corridor from Germany to Gdansk through Polish territory are a cause of a very tense relationship between the two countries.

World War II starts on September 1st 1939, where German soldiers and navy attack Westerplatte and border crossings to Poland. The defence of the Polish post office in Gdansk has been described in Gunter Grass’s novel, The Tin Drum. In March 1945, Gdansk suffers severely under Soviet bombardments and subsequent plundering. The medieval parts of Gdansk are destroyed almost 100%.

After having been liberated from German troops, Gdansk is incorporated into Poland and almost all German speaking inhabitants are expatriated to Germany. At the same time, Polish refugees take up a quarter in the town. The Gdansk Shipyard is quickly brought to function again, which is a cause for a high activity level in the entire region; institutions of higher education (e.g. the Technological University), as well as heavy industry, start functioning again very quickly. Gdansk, Sopot and Gdynia are joined together with a common infrastructure, and the area becomes one of the most dynamic places in post war Poland.

The reconstruction of Gdansk

The medieval centre is reconstructed after the war with respect for its original style. Reconstruction of the centre takes place quite quickly after 1945, but even now, there are areas on the outskirts that need to be reconstructed. The latest big reconstruction was finished around the year 2022.

Since the 1960s, Gdansk has been the seedbed of regular unrests among industrial workers, which culminated in the1980s with the establishment of the trade union Solidarity, and subsequently martial law in Poland in the years 1981-1983. In 1989, Solidarity and the later President Lech Walesa were the main forces behind the changes of the political system which shortly afterwards would change all of Europe and the rest of the world.

After the change of system, Tri-City has continued it’s development towards the bringing about of a modern harbour , among others through substantial expansion of the container terminal in Gdynia. The area also puts more and more emphasis on tourism, and within the last few decades a large number of tourist hotels have been built along the coastline.

Please send an email to m@hardenfelt.pl if you would like an English-speaking tour guide to show you the most important places in Warsaw.