The reconstruction after WWII

#Warsaw tour guide #Warsaw city guide # guided tour in warsaw #Warszawa tour guide #Warszawa city guide #guided tour in Warszawa

Before the outbreak of World War II, Warsaw was sometimes romantically referred to as the “Paris of the East”, and if you walked around some of the elegant areas of Warsaw in 1938, such as Aleja Jerozalimskie or Marszalkowska, you would come across well-kept and beautiful patrician properties. Regardless of the stories of how completely Warsaw’s city centre was destroyed during WWII many of those buildings are still there, giving you the feeling of elegant, dignified and wealthy neighbourhoods. However, it was a small part of the city.

In general, Warsaw 1938 was overbuilt with old, unhealthy apartments. The city had also been growing and the economy couldn’t keep up with the new construction, so a third of the city’s streets consisted of stamped earth roads with no cobblestones or tarmac. This was partly the result of the fact that up until 1931 there was no city plan, so buildings were built wherever they could be and there was no architectural coherence in the buildings. The Old Town – now Warsaw’s pride – had fallen into slums, and although the exterior of the buildings had been renovated and the city walls repaired in the interwar period, the interiors remained dilapidated and inhabited by a poor proletariat. In 1930, the municipality owned a modest 4% of all plots in Warsaw, a figure that doubled to 8% by the outbreak of war under the leadership of Mayor Starzyński. But it was still insufficient to ensure a comprehensive plan for the city.

Above, an image from Rynek in 1938

Post-war city planners therefore saw the destruction as an opportunity to create a new, citizen-friendly city. Some of the urban planning was inspired by Stalin’s real socialism, but there was some freedom in the reconstruction and local architects had a decisive influence on the construction of the new city.

Warsaw had been destroyed several times during the war. Firstly during German air raids in 1939, then during Soviet air raids in 1941, after Hitler had attacked Stalin’s empire. All buildings within the Jewish ghetto were completely dismantled after the Jewish uprising in 1943, however, the worst devastation fell on Warsaw in 1944 and January 1945 after the Warsaw Uprising was crushed. Hitler saw the uprising as treason and decided to punish the city by systematically destroying it. It was predominantly the western part that was destroyed, as the Red Army stood on the eastern side of the river, where much of the city survived relatively unscathed. A large number of calculations have been made of the percentage of destruction, but in my opinion it is difficult to put a percentage on this and the calculation methods were often relatively random. But we can conclude that the city was severely damaged and that parts of it were almost completely destroyed and not suitable for rebuilding what had been there before. Around 84% of all buildings on the western side of the river were damaged to a greater or lesser extent after the war. On the other hand, there were a number of undamaged state buildings that had been used by the Germans, and the water supply, sewerage, electricity and telephone networks were in a condition to be utilised relatively quickly.

However, we’re in the final stages of the war and the Germans simply didn’t have the resources to destroy the city in the way Hitler wanted – much of the destruction was done by setting houses on fire, causing massive devastation. However, the more solid structures could be restored even after a fire.

After the war, all plots of land in Warsaw were nationalised, which allowed for a comprehensive urbanistic plan to be implemented without having to fight with private owners. In principle, they didn’t want to preserve old rental properties, especially if they were of poor quality. Here, the line was that they should be demolished and something new rebuilt on the site. Many of the buildings had missing walls and roofs, windows were gone, everything was damaged. However, many Poles returned to their pre-war homes, and even though they were often dangerous to live in and probably not really suitable for human habitation, people moved in and started refurbishing the buildings.

This private reconstruction was not something the authorities supported, but on the other hand, they could not directly prevent it. No one had anything, labour was cheap. People worked for a bowl of soup, it was all about survival. Work and leisure activities merged into one – surviving and rebuilding. And the building materials were found in the ruins, where everything that could be recycled was recycled. Over time, the authorities realised that the remaining square metres were needed, and citizens were accommodated wherever possible. No one was allowed to live in an apartment by themselves; every spot was utilised.

The private reconstruction also meant that things were not as planned as they had been in the final days of the war. The new Warsaw became entangled in the old, forming the disorganized structure that you can still see when walking through the city.

There were ideas to locate the capital somewhere else, such as Lodz, which was not very affected by the war and had the necessary infrastructure. However, Stalin saw Warsaw’s status as the capital as crucial to the legitimacy of the government and ordered the reconstruction of the capital as soon as possible, and the fact that there was a Polish government-in-exile in London, which was to be stripped of any legitimacy, may also have played a role here.

In these first years after the war, the city was a vast ruin and construction site. As mentioned, all building materials were recycled and there was a constant cloud of dust in the air. Some sources claim that each resident of the city annually inhaled the equivalent of two bricks. Building materials also came from other parts of the country, primarily from the former German territories in the West. This is where the slogan was coined: “The whole nation is rebuilding its capital”, prompting people to gather rubble, which was loaded onto railway wagons and transported to Warsaw. In many buildings from that period today, you can drill into the wall and find the old bricks, and the wall is not necessarily constructed from the same type of stone. In other words, you took what was available.

The idea in the reconstruction was to utilise the situation to create a cohesive city with more distance between buildings and more recreational areas. Emphasis was placed on the renovation and creation of new parks, and many of the existing ones were expanded. This policy is the direct reason why in today’s Warsaw there is always a large green space within walking distance.

In addition, they wanted to maintain the city’s character as an industrial city, thus providing housing for a large working-class population. However, the housing in the city centre was predominantly allocated to people who worked in the state or city administration, and in practice, Warsaw’s city centre was emptied of the lumpenproletariat that dominated before the war. Instead, they were squeezed into apartment blocks in the suburbs.

Walking through the centre of Warsaw today, you will see three main types of architecture. One is the rebuilt Renaissance houses, which are mainly found in the Old Town and Krakowskie Przedmiejsce (the street leading to the Castle Square). Furthermore, the rebuilt Renaissance can be found in a slightly more modest form in New Town (next to Old Town) and Nowy Świat (which is the extension of Krakowski Przedmiejsce). The Mariensztat neighbourhood below Castle Square relates to some extent to 18th century housing construction. It is the historical part of the reconstruction, which should emphasise the national element. In general, the Renaissance can be found in many restorations of historic buildings, including Łazienki Park just outside the city centre, which Poland’s last king had turned into a magnificent park in the 19th century.

The second type of architecture is surviving pre-war buildings, which today are mostly restored. As mentioned, after the war, they were restored to a condition that was just enough for residential use, but were then allowed to fall into disrepair for the next several years. Only in the last ten years have these old houses started to be renovated in earnest, some of which are now gems in their own right. They are abundant on Praga on the eastern bank of the river, but can also be found on Aleja Jerozolimskie (opposite the Central Railway Station and the Palace of Culture) as well as on Poznańska Street and in the side streets of Marszałkowska Street. Another great example of pre-war architecture can be found in the old Jewish neighbourhood around Plac Grzybowski (Metro Świętokrzyska). Away from the city centre, some pre-war architecture can also be seen in the Mokotów district, but it is somewhat less impressive than the areas in the city centre.

Finally, we see Stalin’s favourite architecture – real socialism – which aimed to show the strength of the working class and, as a side note, remind Poles of which ideology and country had the dominant influence in Poland. The most obvious examples are the Palace of Science and Culture (Metro Centrum) and Plac Konstytucji (Constitution Square, metro Politechnika), but much of Warsaw’s city centre is dominated by these mammoth prestige buildings. These are both residential buildings and, of course, government buildings to emphasise Warsaw’s status as the capital city. One of the most perfect examples of the architecture of power is the White House – the headquarters of the Communist Party in post-war Warsaw, located at the roundabout with the palm tree where Nowy Świat and Jerozolimskie Avenue intersect.

Of course, education was also a top priority after the war, and somewhat symbolically, the Polytechnic Institute is located right in the middle of the socialist construction around Constitution Square, while the University and humanities are located in the centre of the Renaissance city.

Above Plac Zbawiciela (Our Saviour’s Square) and below Plac Konstytucji (Constitution Square), both rebuilt in Stalin’s preferred socialist style.

The residential areas outside the city centre and the surviving urban neighbourhoods were planned as clusters of housing that would provide everything needed for daily life, i.e. shopping, doctors, schools, kindergartens and recreational areas. Such a collection of buildings became a small town within the city, and the style survived until long after the change of system in 1989, although it was recognised that many people still preferred to solve their daily needs in the city centre.

You see it all in the local descriptions in my Warsaw guide

I give a detailed description of the different buildings on the routes indicated in my guide – primarily at the individual metro stations, the Old Town, and the King’s Route.

There is no doubt that the rebuilding of Warsaw was characterised by politics. The Old Town pressed the national keys while the socialist buildings showed that a change of system had taken place. There was a certain rivalry between architects who were afraid that Warsaw would look like a museum of the Renaissance and those who were afraid that it would end up as impersonal monoliths and concrete. But even this rivalry wasn’t something that pushed the overall goal. Stalinist president Bierut published a catalogue book in his own name, almost like a bible, showing pictures of the destruction, presenting his vision for the rebuilt city and sketches of future architecture. Occasionally, there were images of Bierut himself standing with a shovel in the heaps of rubble, clearly making his physical contribution to the rebuilding of Warsaw.

The city’s urban architect Jozef Sigalin also published a book – but this one was a children’s book – entitled “five meetings”, in which he described his collaboration with President Bierut. In it he writes:

“Our first building master” – that’s the term construction workers in Warsaw use to refer to him on a daily basis.

“Our first city planner” – that’s the term Warsaw architects use on a daily basis when talking about him.

And the kids? – what do the kids call him?

The kids simply say: “Our friend, our beloved President Bierut”.

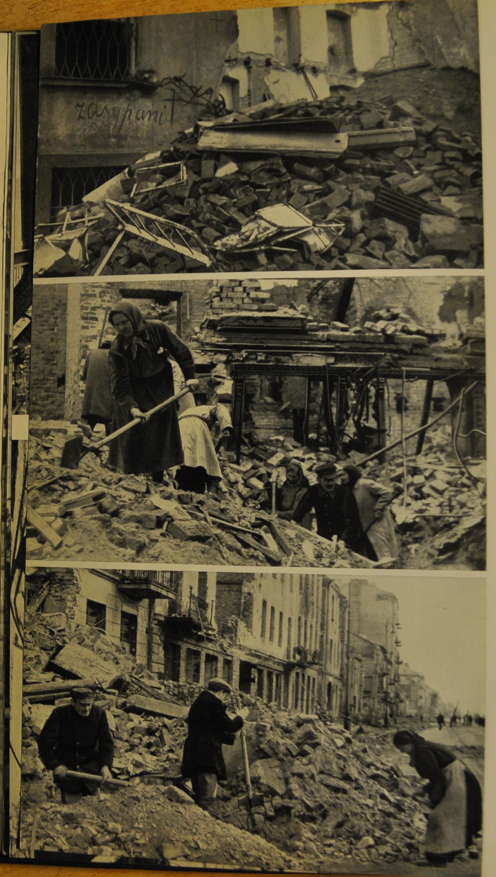

Above, a page of images of destroyed Warsaw from President Bierut’s personal architectural book of testimonies and visions for the capital.

Please send an email to m@hardenfelt.pl if you would like an English-speaking tour guide to show you the most important places in Warsaw.