Warsaw through the ages

A short story made a little longer

Warsaw history – A chronological overview of Warsaw’s history from its founding around 1300 to the present day. A modern city that has experienced devastation.

#Warsaw tour guide #Warsaw city guide # guided tour in warsaw #Warszawa tour guide #Warszawa city guide #guided tour in Warszawa

This was supposed to be a brief overview of Warsaw’s history. The chapter isn’t as short as I would have liked, but what’s here helps you understand the city and the rest of the descriptions. A trip through Warsaw is history and the city’s history is closely linked to the history of Poland. So the concept is that I’ll just provide the most important background information here, and apart from that, we’ll find the story as we move around the city together.

Humans have lived in the area since the ice retreated at the end of the last ice age around 12,000 years ago. The river was much larger and more powerful than it is today, and its waters provided a livelihood for the people of the time. A few thousand years before our era, the area was used for agriculture and cattle farming, and during the Roman Empire it was part of the Amber Route from the Baltic Sea to Rome.

Around the year 1300, the city of Warsaw emerged, probably as both a defensive bastion against Lithuanians and a trading post. Before that, however, a large number of settlements and villages had sprung up within the area where Warsaw is located today. The city belonged to the independent principality of Masovia and in 1339 was the centre of a famous trial between the Crusaders of Pomerania and the Polish state, which was judged by the Catholic Church and conducted in the Church of St John the Baptist, now the city’s cathedral.

The city was very successful and around 1400 a counterpart was built and named the New Town, while the original city was called the Old Town and was surrounded by thick walls. The two cities existed side by side as independent organisms until 1795, when they were united into one entity. The city was ravaged by fires and in 1431 it was formally forbidden to build wooden houses, but it took many years for the ban to be enforced, apart from the Town Hall Square (Rynek) itself.

The city was ideally situated as a trading station between Vilnius and Wroclaw and for the grain trade to Gdansk, and it became a local centre for craft production, both in the city itself and in surrounding satellite towns that were not subject to the strict rules enforced by the various guilds. The city also thrived because of the castle, which had become a regional headquarters, and thus both a base for trading luxury goods and an intellectual centre, with a lot of people who had been educated in Krakow or at foreign universities.

Until 1526, Masovia was formally independent from Poland, but in 1524 and 1526 respectively, the last princes of the ruling line, brothers Stanislaw and Janusz, died and the principality was incorporated into the Polish crown. A few Jewish settlers arrived and competed with the local merchants, and in 1527 the king succeeded in issuing a non tolerandis Judaeis – “Jews are not accepted” in the city. The king spent more and more time in Warsaw, which was centrally located in relation to Lithuania, which was in a personal union with Poland, but there were political forces working for the full unification of the two countries.

After the personal union between Poland and Lithuania was successfully transformed into a real union in 1569, Warsaw became the seat of the main parliamentary assemblies, consisting of the King, the Deputies Chamber and the Senate. This obviously increased trade, but also caused suffering for the citizens, who were forced to house the many visitors during parliamentary sessions. According to accounts of the time, the travelling nobles often behaved like despots during their stay in the houses of the non-noble citizens. The city’s merchants were not of noble birth, because apart from agriculture and grain trading, trade was considered a humiliating and degrading occupation for a Polish or Lithuanian nobleman.

In 1572, the last king of the Jagiellonian dynasty, Sigismund 2. August of Poland, died. In Europe, conflict raged between Protestants and Catholics, but in Warsaw, before the election of a new king, the Sejm decided to introduce religious tolerance, committing to accept all Christian religions. It was also the moment Poland introduced elective kings, although the goal for a long time was the introduction of a hereditary dynasty. However, this never really happened, and from that moment onwards, the central power in Poland weakened, while the lords and regions gained more and more power.

In 1587, the Swedish Sigismund 3. Vasa was elected the first Polish king of the Vasa dynasty, and when in 1596 a fire broke out at the Wawel Castle in the capital, Cracow, Sigismund III moved his address to Warsaw, which was then the seat of parliament and royal residence, while Cracow formally remained the capital until 1795. In the years 1592-1599, the son of the Swedish king was also king of Sweden, which during this period was in a personal union with Poland-Lithuania. However, as a staunch Catholic, Sigismund III was deposed by the Protestant Swedes, which started a protracted conflict between Poland and Sweden.

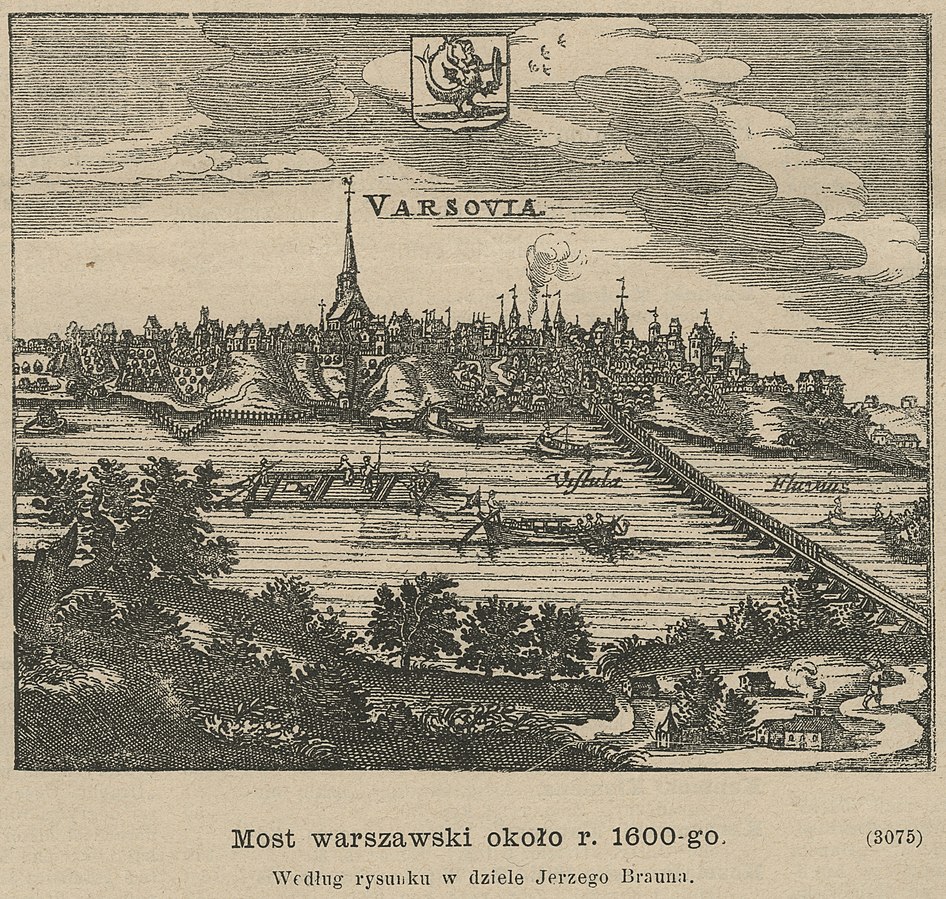

Around this time, Warsaw was a buzzing commercial and artisan city and administrative centre with 10,000 inhabitants. However, Warsaw was still far behind the former capital and university city of Krakow, which had 17,000 inhabitants, and even further from the international trade centre of Gdansk, which in 1600 had 50,000 inhabitants. The city’s population was maintained to some extent by newcomers, as regular epidemics and natural disasters claimed many lives in the city. The first bridge over the river was destroyed in 1603 – thirty years after its construction – by an unusually harsh ice winter. After a major fire in 1607, the architectural expression of the city changed, as the new Renaissance houses after the fire mixed with the former Gothic style in the city centre, which were predominantly designed by Italian architects. The Italians also left their mark on statues and art in the city. It was also during this period that new schools were opened in the city, and from 1624 the first printing house was in operation, authorised to print anything it wanted as long as it did not go against the Catholic faith. At the time, religious tolerance had been limited in the city of the Catholic king, and only Catholics could be granted citizenship in Warsaw.

The bridge across the river, around 1600. A short-lived pleasure

It was a turbulent period with civil war following the election of Sigismund and war with Sweden. A Swedish-Russian alliance led to war with Russia and in 1611 the Russian Tsar was taken captive to Warsaw, where he was presented to the Sejm. The Russian Tsar died in Polish captivity and the Russians elected a new Tsar of the Romanov dynasty, who would go on to make Russia a great power for the next 300 years.

Jan Kanty Szwedkowski, Hołd carów Szujskich. The Russian car in captivity in Poland is still a traumatic experience in Russia.

The Vasa family managed to have three kings on the Polish throne and remained in power until 1668. Despite numerous wars, the city developed dramatically during this period; luxury goods and heavy weapons were traded and produced, and new villages and production centres developed around Warsaw.

In 1648, Cossack leader Bogdan Khmelnytsky rebelled and established a Ukrainian state. Warsaw was in panic because of rumours that the rebels would head towards Warsaw, but this turned out to be false. On the other hand, Warsaw would suffer because of wars, civil wars and plague for a long time to come, and in 1652 the liberum veto was used for the first time. The liberum veto was the right of a single member of parliament to prevent the implementation of laws, and this institution would be used frequently over the next hundred years+, contributing to the process that led to the total collapse of Poland in 1795.

Khmelnytsky – evil man and traitor in Poland, a hero in Ukraine

In 1655-1660, the Swedes and their allies visited Warsaw three times, where the soldiers ravaged, looted and burned down parts of the city. The widespread devastation is a frequently repeated theme in Polish literature and film, so the Swedish “deluge” as it is referred to in Poland is a clear part of the historical consciousness in Poland. In 1660, however, the Peace of Oliwa was signed, allowing Warsaw to proceed with the rebuilding of the city. This led to the development of the Rococo style, of which King Sobieski’s summer residence from 1680 is a prime example. From 1697-1764, Poland was in personal union with Saxony (interspersed with periods of counter-king rule during civil wars). During this period, both kings and high nobility built a number of mansions and castles in the city, and from 1700 to 1792 the city’s population tripled from 40,000 to 120,000. There was still no university in the city, but monastic orders provided basic education for the children of wealthy people. It was also the Piarist Order that published the first nationwide newspaper, “Kurier Polski”, in Warsaw from 1729.

In 1764, Stanisław Poniatowski acceded to the Polish throne after pressure from Russia. He had previously had a love affair with Catherine II of Russia, who thus installed his ex on the throne of what has now become a Russian puppet state. Poniatowski dreamed of reforms, but was quickly told to get busy with something constructive and stay away from politics. The king set about creating parks, building mansions, renovating castles and employing painters. A prime example of the king’s artistic pursuits is the Łazienki Park (Royal Baths), which today is located just outside the city centre in the Mokotów district. Here, every flower bed and clump of trees was composed with great artistry, mansions, amphitheatres, indoor theatres and much more were built. The whole thing was divided into sections so that at times you could feel like you were in ancient Rome, at times you were travelling to China. But in general, the building style was inspired by antiquity, and the vast majority of what was built under Poniatowski was neoclassical. The king was effectively the head of a powerful Ministry of Culture, and this spurred the rest of the Polish high nobility to rival the king in artistic opulence. Although the king had no significant political influence, Poniatowski did manage to open the first secular school in the city, the Knights’ School, which would prepare young nobles to serve in the military and politics.

It was also during this period that the main streets of the city were paved, but the vast majority of Warsaw still consisted of hard stamped earth. They also started building on the banks of the Wisła River. Even today though, the river banks have not really succeeded in becoming a part of Warsaw.

After the Pope abolished the Jesuit order in 1773, the entire education system in Warsaw collapsed, but was immediately replaced by a secular “National Education Commission”, which was later labelled “the world’s first ministry of education”. Overall, the air was thick with conspiracy and desire for change, both modernising the way the state was run internally and resisting Russian dominance.

In 1772, 1793 and 1795, Poland was divided three times, with the country’s territory split between Russia, Prussia and Austria. The 1793 partition came after Poland adopted the first modern European constitution in 1793, just after the implementation of the US Constitution. It did away with the old idea that Poland and its inhabitants were the property of the nobility.

Prior to this, from 1789, there was a Sejm, known to posterity as “The Great Sejm”, which sat until 1793. Shortly after the Sejm was assembled, a delegation of citizens arrived at the castle where the parliamentary session was held. The delegation has been dubbed the “Black Procession” after the black clothing worn by all participants. They demanded personal freedom and political reforms, which were incorporated into the work of the Sejm during the next two years. In general, it was a turbulent period, as America had seceded from England and become a republic. At the same time, the revolution was raging in France, and the radical revolutionaries also inspired part of Warsaw’s population.

Stanislaw Bagienski: The Black Procession, 1789

In April 1791, a new law was passed granting citizens a number of rights, and on 3 May of the same year, the 3rd of May Constitution was passed. Apart from the introduction of a hereditary kingship and universal suffrage, the Old and New Towns were merged into a single entity, along with all the independent small towns that surrounded Warsaw. Soon after, the administration tried to bring some order to the city, and all beggars and idlers were either sent to forced labour or – in the case of the old and sick – to poorhouses.

The new liberal currents were equally unacceptable to Russia and some of the Polish nobility, who rebelled against the changes. It didn’t help matters that Warsaw was buzzing with radical insurgent tendencies. Warsaw was occupied by Russian troops, after which Russia and Prussia jointly carried out the second partition in 1793. This was the beginning of a downturn, with many citizens leaving the city and a large number of businesses going bankrupt after losing their customer base.

The response to partition was the Kościuszko Uprising, led by a Pole who had just fought in the American Revolutionary War. In Warsaw, the uprising was led by shoemaker Jan Kiliński, who managed to get a large number of the city’s craftsmen to join the rebellion. However, after seven months, the uprising was crushed, the final partition was carried out in 1795, and Warsaw ended up as a sleepy outpost of the Prussian Empire.

Jan Matejko, Collapse of Poland, painted 1866

King Poniatowski lived his last years at court in Russia, while Warsaw was reduced to a dusty provincial town where all officials were German. The population was halved to 65,000 inhabitants, but the city was, as usual, made up of immigrants, as wars and epidemics tended to regularly wipe out a large portion of the city’s citizens. However, improved sanitary control and smallpox vaccination of citizens improved survival rates, and the introduction of the possibility to register mortgages in 1797 was essential to the credit system.

Napoleon sought to spread French civilisation across Europe through war and came to Warsaw in 1806. Here he took a Polish mistress, whom he called “my Polish wife”, and in 1807 he established the Principality of Warsaw in personal union with his ally, the German state of Saxony. The new prince was the grandson of August III of Poland, who had ruled until 1763, so there was some continuity here. Napoleon personally dictated the constitution of the principality and introduced his great civil code, the Napoleonic Code, which was groundbreaking for its time and remains the basis of civil law in Europe and much of the rest of the world.

Although the Poles put their faith in Napoleon as a liberator and the French Emperor needed Polish soldiers, Warsaw suffered from being treated as an enemy city. The French soldiers were known to commit murder and rape as they searched the houses for valuables to loot.

However, the principality became history when Napoleon met his Waterloo in 1815, and the Congress of Vienna then created the Kingdom of Warsaw, which became subject to the Russian Tsar. In the decades to come, the people of Warsaw continued to regard Napoleon as a liberator, dreaming that one day one of the emperor’s descendants would come to liberate Poland from the Russian yoke.

Warsaw became the capital of the small Kingdom of Poland and the Russian Tsar became the sole ruler, but still gave the country a constitution and a parliament with limited rights. Initially, state administration offices were occupied by Poles and there was freedom of the press, but this was quickly curtailed. The reduction of tariffs on goods exported to Russia boosted trade and industry began to flourish in the city. The period was characterised by many predominantly Jewish newcomers and an expansion of the city’s boundaries. Some major building projects were also initiated. The Stock Exchange and the Great Theatre was built, and a university was established.

Romanticism reigned supreme in music and literature during this period, and the large buildings that were constructed were predominantly in the classicist style. Music played a major role, and it was in music that little Fryderyk Chopin would grow up, having been born in 1810 into a Franco-Polish family with strong Polish nationalist views. Chopin composed as a child, attended the music academy and played in the mansions, but in 1831 he left Poland just before the outbreak of an uprising that resulted in him never returning to Poland.

The November Uprising of 1830-1831 was centred in Warsaw and lasted just under a year. The uprising led to the cancellation of the constitution, high tariffs on exports to Russia and the abolition of Polish autonomy. The punishment for participating in the uprising was deportation to Siberia and confiscation of property, which affected a large number of Polish nobles with large land holdings. After the uprising, Russia began the construction of an enormous citadel on the banks of the Wisla River, a military barracks that was aimed directly at the city of Warsaw and would be expanded many times over the coming years. It wasn’t until 1850 that customs duties on exports to Russia were lifted again, and around the same time the city felt the dynamism of the newly established railways, which helped turn Warsaw into a trading hub. Newcomers continued to arrive, and by 1864 the city had 222,000 inhabitants, a third of whom were Jews, who predominantly settled in their own neighbourhoods and spoke their own languages. It was during this period that Warsaw transformed into a true factory city. In 1864, the first steel bridge over the river was handed over, connecting Old Warsaw to the Praga district. At the same time, street lighting was established in the form of gas lamps.

However, Russian censorship and control of citizens was oppressive, and the secret police took up a third of the city’s budget.

The January Uprising of 1763 lasted until the autumn of 1864, again making Warsaw the rebel capital of the National Government. The rebellion took the form of a guerrilla war and was met with counter-terrorism from the Russians, as well as random arrests and house searches.

Anonymous: Russian soldiers capture Polish children in Warsaw 1831. Several thousand Polish boys between 7 and 16 were enlisted in a special battalion of Polish children of rebels, orphans and other able-bodied soldiers.

The uprising again led to violent reprisals, with arbitrary executions and exile to Siberia taking place during the ensuing martial law. The vast majority of Polish institutions were closed down, and a total Russification of the Kingdom of Poland was pursued, including Russian-language education in all schools. In principle, martial law remained in force until the first world war. However, it was a period when national sentiment was awakened across Europe and Russian oppression was responded to with secret Polish lessons.

Russification did not stop the industrialisation of Warsaw, which developed into a supplier of goods for the entire Russian Empire. In 1880 a telephone company was established, from 1884 horse-drawn trams operated and the city grew with new industrial workers, but conditions were not good. On average, three people shared a room, and although 34% of buildings in 1890 had running water, only 6% had sewerage. The sanitary conditions in the city were the direct cause of typhoid and tuberculosis outbreaks.

In Russia, revolution broke out in 1905 in the wake of the Russo-Japanese War, where Russia emerged as a colossus on clay feet. In sympathy with the crackdown on protesters in Russia, strikes broke out in Poland and on 28 January, 400,000 workers, schools and universities went on strike demanding Polish as the language of instruction. It had also been a tough couple of years, as in 1903 food prices skyrocketed due to flooding and in 1904 there was a drought. The school strike spread across Warsaw and lasted more than three years, with parents refusing to send their children to Russian-speaking schools.

The conflict developed into a struggle between an economic elite against the workers, who fought for the recognition of their social rights. A huge undergrowth of political parties and movements emerged, while the most serious battles were not between Poles and Russians, but between nationalists and socialists, who fought each other with their terrorist organisations. Part of the socialist faction broke away in 1906 and joined the Russian Bolsheviks. Thus, they were no longer fighting for Polish independence, but for Slavic socialism.

The Tsar was pressured from all sides by war and rebellion, and during 1905 Polish was allowed in private schools, trade unions were accepted and religious tolerance (limited conversion between Christian denominations) was introduced. At the same time, the previously extensive preventive censorship was restricted. In October, the pro-Russian nationalists were promised a constitution and a consultative national assembly in Russia with Polish participation. In April 1906, elections were held for the first National Consultative Assembly (Duma). However, it had no legislative initiative or concrete powers and functioned more like an assembly of estates. The events of 1905 opened the door to a popular rebirth of Poland, with cultural centres and local administration in Polish.

Meanwhile, a huge Russian church was under construction on what is now called Pilsudski Square, symbolically chosen to be located right next to the palace of the Saxon kings. Completed in 1912, the church symbolised Russia’s supremacy in the city, just as the Palace of Culture came to symbolise it in the post WWII era. In 1915 – in the middle of World War I – the Warsaw Polytechnic Institute was established.

The divisions between supporters of East and West continued during World War I, with the nationalists supporting the Pan-Slavic movement and recalling the newly invented “eternal enmity with the Germans”, while the socialists were in a loose alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary. Here, the later freedom hero Pilsudski set up shooting clubs and organised sabotage against the Russians. Meanwhile, all warring parties promised autonomy to Poland after the war, and all schools in Warsaw began teaching in Polish. However, the Russian warfare did not go well, and in 1915 the Germans moved into the city, which was allowed to govern itself and set up a city council, but otherwise suffered from the wartime economy. Inflation was huge and the many unemployed were fed from mobile soup kitchens.

Most Polish and foreign actors envisioned a future Poland as an autonomous territory under Germany, Russia or Austria-Hungary, while the rebel Pilsudski refused to go under German command. He was therefore interned in Germany during the war, while the freedom movement in Warsaw strengthened in line with the occupying powers’ unfortunate warfare. In 1917, US President Wilson spoke of an independent Polish state with Warsaw as its capital, setting the agenda for future political developments. Meanwhile, the Warsaw City Council laid the framework for future municipal self-government.

Towards the end of 1918, Russia was losing World War I and Germany was about to collapse. Several Polish provisional governments were established, of which the one in Warsaw undoubtedly had the most legitimacy. When Pilsudski was released from German internment in November 1918, it was the latter who gave Pilsudski the military leadership of the newly created Poland, which he was able to rule with almost dictatorial powers during this first period.

As the capital of the newly independent Poland, Warsaw’s population nearly doubled to 1.3 million over the next twenty years, while the Jewish population decreased from 42% to 29% over the same period. In general, the time was characterised by tensions between nationalistic Poles and other peoples, as evidenced by the assassination of Poland’s first president Narutowicz, who was shot by a nationalistic Pole who could not accept that the president was elected with ethnic minority votes. The tensions reinforced the separation that existed between Jews, other ethnic groups and Poles, many of whom found it difficult to accept that a Jew could be a Pole.

General Haller and Poland’s strongman, Marshall Pilsudski after the victory over the Russians in 1921, Public domain.

Political tensions culminated in a coup in 1926, when rebel leader Pilsudski held a famous meeting with legal president Wojciechowski on one of the bridges connecting the two parts of Warsaw. The period from 1926 to the outbreak of war in 1939 can be described as a quasi-democracy, where the country tried to manoeuvre between neighbouring authoritarian states.

A number of modernist buildings were constructed, while Russian buildings were remodelled into Polish style and the huge Russian church on what is now Pilsudski Square was demolished as a symbol of Russian domination. However, balancing the budget was an almost impossible task, and due to the strained economy, the government appointed a commissioner as mayor from 1934. It was the energetic Stefan Starzyński, who is popularly referred to as the mayor of Warsaw, although he was actually a government official. He modernised the administration and tried to make sense of the chaotic construction going on around the city. During this period, attempts were also made to modernise the dilapidated Old Town, which had sunk into a cheap marketplace for the city’s proletariat.

The anticipated attack from Germany began on 1 September 1939, and in the first phase of the war Warsaw was hit by a series of bombings that damaged the airport and the Royal Palace in the city centre. A citizen’s army was quickly set up, digging ditches and building tank shields, but on 1 October, the Germans entered the city.

The long-term German plans were to create a smaller German city and otherwise remove anything resembling Poland. From the beginning of the occupation, a Jewish ghetto was created and the population was systematically transported from the ghetto to extermination camps.

Throughout the occupation, Warsaw was the headquarters of the Polish resistance movement, which co-operated with the Polish government-in-exile in London. Frequent actions forced the Germans to place large army units in the city to keep it under control.

The city was held in an iron grip, people were arbitrarily rounded up on the streets and sent to forced labour in Germany, and the rest worked locally for starvation rations that forced people to buy smuggled goods to survive. In this way, citizens quickly lost all valuables, which were exchanged for food.

Warsaw was characterised by two major uprisings during the occupation; the Jewish uprising in the ghetto in the first half of 1943 was a suicide operation where the Jewish militia decided that it was better to die in battle than to be transported to extermination camps. The Warsaw Uprising, on the other hand, took place at the end of 1944 and aimed to solidify the Polish rebel movement’s rule in Poland after the war. However, the rebellion needed the support of the Red Army to maintain power in the city. Stalin did enter the Praga district, but did not cross the river until the rebellion was crushed. It wasn’t until 17 January 1945 that the Red Army entered Warsaw, from where the Germans were fleeing.

The ruined city became the capital of the new Soviet-dominated Poland in 1945, although there were proposals to make undamaged cities such as Lodz, Krakow or Poznan the new capital. However, Warsaw’s historical role became crucial here, as it was important to show that the Nazis did not succeed in exterminating the city, that their fight against Polishness was in vain. The few people who hadn’t fled or been killed lived mostly on the eastern riverbank or in suburbs far from the centre, but refugees quickly began to return and the work of digging bodies out of the ruins also began as the clean-up progressed.

The rebuilding of the city was centrally planned, with talks of an “architectural recovery”, i.e. a certain orderliness in construction and a lower population density than before the war, resulting in the prioritisation of open spaces and the expansion of existing parks and the creation of new green spaces. Warsaw was in a privileged position compared to the rest of the country because a large part of the state funds for reconstruction went to the capital, and the national slogan “The whole nation rebuilds its capital” was used to collect usable building materials from the ruins of other Polish cities and forward them to Warsaw. The planned reconstruction made it easy to implement the nationalisation of all land and real estate in Warsaw, which also harmonised with the government’s ideological foundation. However, the promised compensation to the owners was rarely paid out.

It was also decided to maintain the city’s status as an industrial city, which required both industrial districts and residential areas for the many physical workers, as the city centre was predominantly inhabited by administrative employees.

Many of the returning refugees also began to renovate their buildings, which was often classified as being in need of demolition. In this way, the rebuilding of the city took place on two levels – the official, centrally decided one and the localised one based on the will and possibilities of the citizens. Building materials were found in the ruins and labour was cheap in the early days when people were happy to work for a bowl of soup; it was simply a matter of survival.

The city quickly revitalised; Soviet army engineers built a makeshift bridge over the river, markets reopened, and in the ruins, enterprising people even opened small cafes. Warsaw, however, remained the centre of various conspiracies. The Soviet-backed government persecuted members of the bourgeois resistance movement, who simultaneously organised resistance against the Red Army and supported the government-in-exile in London.

The reconstruction immediately after the war consisted predominantly of Renaissance buildings in the old town, where the façades were to some extent faithful reproductions of the previous appearance of the destroyed buildings. Furthermore, large parts of the city centre and government buildings were constructed in socialist realism, Stalin’s personal form of modernism, which used columns and monumentalism to remind the people that it was now the worker who owned the palaces and was the leading force in the socialist empire.

The 1970s brought concrete buildings to the capital, which were placed in large quantities in the suburbs. This brought relief to the crowded housing situation, but the city continued to grow, so there was constant competition for apartments. In turn, allotments became the solace for many, especially those who had moved in from rural areas, and these small garden areas with their sheds can be found all over Warsaw today.

It was also during this period that a number of new express roads were built, the Royal Palace in Warsaw was rebuilt, the city got a new modern main railway station (which today seems less modern) and the airport in Okęcie was expanded. However, the airport is surrounded by the city, so there was limited room for expansion and Warsaw never became a central transport hub.

As in a number of Western European countries, a student uprising broke out in 1968, but it was brutally suppressed and the authorities scapegoated the remaining Jews, resulting in a significant emigration of Polish Jews to Israel, the US and other countries, including Scandinavia.

After the 1989 roundtable talks, Warsaw became the capital of the new west-orientated Poland. Like everywhere else in Poland, real wages fell dramatically in these early years, while shops were filled with goods that had previously been impossible to buy in stores. At the same time, private developers began building new residential areas and high-rise buildings in the centre of Warsaw, and a number of statues were erected that had not been built before, so as not to offend the Soviet Union. One of the biggest capital investments in the new Warsaw was the metro, which the city had been struggling to built since before WWII.

Please send an email to m@hardenfelt.pl if you would like an English-speaking tour guide to show you the most important places in Warsaw.