Communism in Warsaw

Admiring the wonders of communism

#Warsaw tour guide #Warsaw city guide # guided tour in warsaw #Warszawa tour guide #Warszawa city guide #guided tour in Warszawa

It’s been almost 35 years since communism was wiped out and many of the architectural expressions of the period have been relentlessly demolished or modernised. However, the architectural fingerprints of the period are still clearly visible in the cityscape.

The fingerprints of Stalin – not only the Palace of Culture

The most obvious example is the Palace of Culture, which is seen by ALL visitors and is almost synonymous with the centre of Warsaw. Marszałkowska Street, with its width and monumental apartment blocks, can actually be considered an extension of the Palace of Culture and was Stalin’s and the Communist Party’s prestige project after the war.

However, the entire urbanistic concept is the work of communist city planners, and it has changed Warsaw from the cramped city it was before the war to an open, bright and friendly city filled with forests and green spaces.

Of course, the city planners were also responsible for the reconstruction of the Old Town, which doesn’t really resemble communist architecture, but was seen as necessary to emphasise the Polish national character of the city. Polishness is emphasised in many places, even in socialist architecture, but entire residential areas were built as Polish Renaissance towns or with mixed architecture, such as Mariensztat just below the Castle Square in Warsaw. It was thus a double-edged architectural message, where citizens had to understand that the system was new, but they also had to realise that they were in their old, safe homeland.

Until recently, Warsaw’s communism was also characterised by the many pre-war buildings that were deliberately not renovated after 1945. Most of them have only been refurbished in the last 10 years, and in some places renovation is still ongoing.

And you can follow the first brick houses from the 1950s and 1960s, through the prefabricated concrete buildings of the 1970s and 1980s.

I have selected a small number of sites that are worth visiting if you want to follow communism in Warsaw. Inevitably, there will be some overlap with other themed articles, but I try to write about the individual objects in one place only and then refer to other articles where they fit in more places.

The Old Town – a rebuilt fairytale town

The Old Town starts with the Castle Square, where the Column of King Sigismund from 1644 along with the Mermaid is a symbol of Warsaw. Many city centres in Poland were rebuilt in a similar style, but I’m not sure if the reconstruction should be placed under ‘Communism in Warsaw’ – so it’s been moved to the ‘Nowy Świat Uniwersytet Metro Station‘.

Rynek – the old town hall square in the Old Town has been reconstructed after the devastation of the war

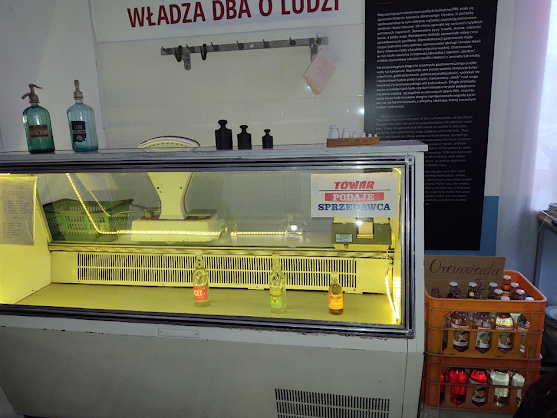

Museum of the Polish People’s Republic

(Museum życia w PRL) Address: Piękna 28/34 (Metro Politechnika) – A small museum with a fascinating collection of artefacts from the Polish People’s Republic, police equipment, everyday items and much more.

You can also see how the flats were furnished during this period. If you’re a little older, you can try to compare with what it was like in your country at the same time. Maybe it wasn’t always so different.

During certain periods there were notorious food shortages and rationing in the Polish People’s Republic, and while people did of course get something to eat, the story is too good not to use when you have a museum about the People’s Republic

A soda vending machine – the glass is chained to the machine

Palace of Culture – the temple of the communism

(Pałac kultury i nauki) and Plac Defilad. Corner of Marszałkowska and Jerozolimskie. Metro Centrum.

The Palace of Culture is both a symbol of Soviet dominance in Poland and a narrative of Warsaw and the city’s history. It is an enormous building – 237 metres high, 123.000 square metres and 3.288 rooms.

The Palace of Culture can be seen from all major access roads. Here from the rear side with the congress hall.

A citizen of the working people familiarises himself with the theories of Marx, Engels and Lenin. If you take a cloze look, you can see that Stalin is chiselled out of the reading list. The People’s Palace itself is a “gift” from Stalin.

The palace of Culture was a symbol of Soviet dominance in Poland

Although the building contains elements with reference to Polish architecture, it is so influenced by Russian style that no Pole under communism would have doubted who was in charge in Poland. The Palace of Culture had the same purpose as the huge Russian Orthodox Church on what is now Pilsudski Square, which was demolished after Poland’s independence from Russia in 1918, and many have talked about demolishing the Palace of Culture. However, it has now stood for over 30 years after the Russians were chased out of the country and is now considered a landmark by the majority of the capital’s inhabitants.

Inside the palace impresses with its splendour, expensive marble and thoughtful interior design

Stalin’s appointed architect Lew Rudniew was responsible for the building

Russian architect Lew Rudniew was responsible for the construction of the building. Directly appointed by Stalin and known for his sculptural constructions in the Russian socialist style, he toured Poland before the construction of the Palace of Culture to familiarise himself with classical Polish architecture, and the building features typical Polish national elements, including the overgrown attika (superstructure that hides the roof).

Inspired by Russian skyscrapers, which were inspired by American towns

The Palace of Culture may look a bit like the first American skyscrapers, but it is definitely inspired by similar buildings in Moscow. On the other hand, the buildings in Moscow are inspired by American skyscrapers – such as the Empire State Building – and Lew Rudniew was one of the architects sent to the US on a study trip to get an impression of American skyscraper construction.

The building fulfils a variety of functions such as cinemas, theatres, restaurants, exhibition halls, a meeting room for the Warsaw City Council and houses a wide range of businesses and cultural institutions, not to mention the viewing terrace at the top, which fortunately can be reached by lift. The viewing terrace provides an overview of the urban planning and logic of the many newly constructed skyscrapers. The building is also equipped with a congress hall, although it was built with socialist congresses in mind and is therefore equipped with a tiny stage so that attendees can focus on the essentials and applaud at the right times. The hall also lacks back stage facilities, that can support concerts or other events.

If you like to stroll, it’s a good idea to walk around the entire building to get a sense of its proportions and enjoy the many details that the low extensions offer. You’ll also realise that the building is almost as wide as it is tall. Pay special attention to the area below the main entrance where the car park is located. Here you will find examples of Polish cars, including the small Fiat (produced in Poland under licence) and the Polish buses, which were called “cucumbers”.

Cucumbers – these are the old Polish buses that can be hired for a tour of Warsaw. Just drop me a line and I’ll help you with the tour.

In front of the main entrance we find the Defilade Square (Plac Defilad), where people stood and admired the communist leaders during the communist era, and the party leaders would wave to the passing working people. The grandstand has been preserved, but a new Museum of Modern Art and a theatre are being built next to it, which will make the square more diverse. The museum plans to open its doors to the public in 2024.

By the wall up to the grandstand is a memorial plaque to Piotr Szczęsny, who in October 2017 set himself on fire and died during a protest against the government’s restriction of democratic freedoms and violation of the Polish Constitution.

Piotr Szczęsny set himself on fire in 2017 to draw attention to the restriction of democratic rights in Poland

Ministry of Agriculture from 1955

Address: Wspólna 30. Metro Centrum or Metro Politechnika.

The Ministry of Agriculture is a huge ministry, and although there are formally more important ministries, it has held a crucial position, especially in Poland immediately after World War 2, where Poland was completely dominated by agriculture.

The building was completed in 1955, and the back side from Ulica Wspólna is particularly striking. The huge colonnades on a narrow street make a strange impression, but the plan at the time was to demolish the ‘old shit’ and build a large square in front of the entrance to the ministry, which never materialised. The facade of Ulica Wspólna is inspired by the old Saski Palace on Piłsudski Square, which was destroyed (and so far not rebuilt) during World War II.

Ministry of Agriculture from Wspólna Street – but the building covers a whole block – 4 different streets

Mariensztat – the countryside in the centre

10 minutes from the Castle Square in the Old Town. Take the escalators.

From around 1550, royal power began to weaken in Poland, while the regions and powerful nobles gained more power. The weakening of central power was evident in a mushrooming swarm of so-called “jurydiki”. These were independent, privately-owned small towns that surrounded Warsaw but were not subject to the laws and regulations of the city itself. They were usually owned by wealthy noblemen, and as they were not bound by the city’s bureaucracy, they were able to sell manufactured goods cheaper than the city itself. The increase in the number of jurydiki increased from around 1650, creating a vibrant competitive situation between the main city and the satellite towns.

The provincial atmosphere is palpable

An example of such a satellite town is Mariensztat, located below Warsaw Castle Square. It was established quite late, in 1762, and sank into a poor neighbourhood that suffered severe destruction after the Warsaw Uprising in 1944. After the war, Mariensztat became the first rebuilt residential area, reflecting the city’s former provincial character, and a social realist statue of a merchant woman symbolises the city’s past as a trading centre. If you’re in the castle square, it’s less than a ten-minute walk each way on the escalators, and it’s a refreshing trip if you’re looking to get away from the Old Town itself.

The square in Mariensztat

National i form, socialist in content

Architecture in 1950s Poland was dictated by Stalin, who saw architecture as the realisation of his vision of society. As a result, Poland erected buildings that were national in form and socialist in content. Not all of them were necessarily concrete palaces. A good example of the style can be seen in Mariensztat, which with its low houses and cosy town hall square is reminiscent of Polish Baroque.

Housing made as copies of the Royal Castle in Kraków

One of the most important buildings in Mariensztat is the “Waweliowiec” at 9 Bednarskiej Street, which with its colonnades is reminiscent of the medieval Wawel castle in Krakow. Here you can see the essence of real socialism – a royal castle converted into workers’ flats.

Housing for working people

Communism in Warsaw – 2 hour walking tour with a guide. Price: 350 zloty

Communism has left a lasting fingerprint on Warsaw. Thorough introduction in 2 hours. Please click at the headline to continue.

The Party House or White House

Address: Plac de Gaulle – corner between Aleje Jerozolimskie and ulica Nowy Świat. Metro Centrum – about 10 minutes’ walk.

A huge modernist building from 1952, which until 1989 was the headquarters of the powerful Central Committee of the Communist Party.

Here, the planners sat in a building that clearly shows where power resides. Entering the building through two gates, the huge courtyard was designed to accommodate a large number of party members who could listen to speeches from the leaders standing on the large balcony. There was everything needed for political education, including a cinema and large meeting rooms.

The White House as seen from Plac de Gaulle

For a period of time after the 1989 changes, the building served as the stock exchange, but today a beautiful new stock exchange building has been erected on the back of the White House. Later, the Department of Agriculture had various offices in the building, which is now rented out for offices and conferences. On the ground floor, however, there are currently four craft beer bars, which in the summer spread out over the front and the entire impressive space of the building. An ideal opportunity to combine beer drinking with reflections on the architecture of power.

The White House courtyard is now occupied by beer-drinking, happy people, but until 1989, bureaucrats sat behind every one of these windows, which also had their own cinema and other facilities. Note the balcony on the left in the picture, where leaders could communicate to the crowd of party soldiers gathered in the courtyard

Plac Konstytucji (Constitution Square) and Marszałkowska Street

Metro Centrum (by the Palace of Culture) or Metro Politechnika.

A classic example of Stalin’s favourite building style – real socialism. The entire area was completed in 1953, the same year the new communist constitution came into force.

The square is built in solid quality with colonnades – this is how the working class was supposed to live in the future

There’s attention to detail. Note the statues on the rooftop

The tall columns clearly refer to the palaces of the past, telling the story that now the people (or perhaps the party) rule. Now ordinary people are allowed to live in apartments that look like palaces from the outside.

It was planned that the whole of Poland would be rebuilt in this way, but Stalin died in 1953, and then they realised how insanely expensive it was to build this way.

The working people are chiselled into the facades

The Entire Nation Builds Its Capital

Like many other buildings from this period, they were built under the motto: “The Entire Nation Builds Its Capital”, which meant that trainloads of rubble from the ruins were sent from different parts of Poland (mainly the former German territories) to Warsaw. As a testament to this, if you pick up a drill today, you can find different types of bricks in the walls in the buildings from that time.

With the construction of the square and the wide boulevard leading to the Metro Centrum, the layout of the streets was changed after the war. However, the old names have been retained, which means that both Piękna Street and Koszykowa Street have an odd alignment on the other side of the square.

Some of the streets were given a most peculiar and interrupted alignment. Here we are in Koszykowa Street, through an open gate from Plac Konstytucji. Here we find houses from before World War II.

Fryderyk Chopin Music University

(Uniwersytet Muzyczny Fryderyka Chopina)

The Warsaw Conservatory of Music was designed in 1959 and completed in 1966, by when Stalin had been dead for many years. With Stalin’s departure in 1953, his socialist architectural visions, which until then had adorned Warsaw with their monumentality, died relatively quickly.

The Music Conservatory (only recently have all colleges been renamed universities) is also monumental, but at the same time characterised by lightness and dynamism. After Stalin, many architects returned to modernism and the building is characterised by the avant-garde that was sweeping Europe at the time. The spiral staircase and asymmetrical forms would have given Stalin a feeling of Western decadence, and the architectural studio’s staff would probably have received a one-way ticket to Siberia if the great Soviet leader had still been alive.

The University of Music – seen from the back

The university is located in the centre of a music district, including the Chopin Museum, the Chopin Institute and apartment blocks with music graffiti and gable murals featuring Chopin. If anyone still thinks Chopin was French, hopefully they’ll change their mind after visiting this area.

Central railway station

(dworzec centralny)

Actually, it’s Warsaw’s Main Station, but since another modest railway station has that name, I’ll stick with the Polish name, Central Railway Station.

In 1967, a footboard was built here, and a few years later – in 1975 – the actual railway station was born. It was a railway station that would show what the communist society could achieve, and it was built in just three years to be ready for the 7th Congress of the Communist Party, which was visited by Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev.

The railway station – here surrounded by buildings from the capitalist period that began in 1989

The railway station was planned at a time when Poland was experiencing a construction boom thanks to large loans from the West, and the railway station was to be a prestige building. The large modernist railway station was equipped with underground platforms and a lightweight – almost floating – superstructure. However, the pace of construction created a lot of shoddy workmanship, and imported electronic marvels from the West stopped working when they broke. Over time, the railway station started to look a bit shabby. The railway station has recently been completely renovated and is now much more open and efficient than before.

Housing construction from the 1950s and early 1960s

Muranów is located on an area that used to be home to satellite towns (jurydiki), which in the 19th century were inhabited by Jewish immigrants from the eastern territories. They came to dominate the neighbourhood, which took on its own cultural and linguistic character.

On 16 November 1940, the German occupying forces sealed off the area and created the Jewish ghetto in Warsaw. I write more about this under “Jewish Warsaw”. In 1943, the confined “inhabitants” revolted against the Germans and persisted from 19 April to 15 May.

As a result, the ghetto was demolished. Any tourist to Warsaw will hear that Warsaw was destroyed after the Warsaw Uprising in 1944. This refers to the rest of the city after the uprising, when the Polish resistance movement attempted to wrest power in the city from the Germans. The destruction in 1944 was significant, but in no way compares to the destruction of the buildings in the Jewish ghetto. In 1944, a lot of buildings were left in a terrible state, but they could be repaired, in 1943 the ghetto was leveled so that all the rubble was at street level.

Some parts of Muranów were erected with inspiration from Stalin’s real socialism

It also made it easy to completely rebuild Muranów without regard to the previous architecture. New streets were laid and the alignment of old streets was changed. After the war, the area was quickly built up with small apartments in a variety of styles, partly to commemorate the Jews who no longer remained and partly to stick to the socialist style, without spending the same amount of money as on the prestige buildings in the city centre.

However, many of the buildings became apartment blocks with small flats

Today, the area is dominated by the Museum of the History of the Jewish People (POLIN) from 2006, which is surrounded by the many residential buildings from the 1950s and 60s and Jewish memorials.

Built with lots of green spaces and balconies

Residential buildings from the late 1960s and later

The prefabricated concrete elements of communism are known for both their ugliness and misanthropic architecture. But are they really that bad? At least they weren’t so keen to utilise every single square metre, leaving air and green spaces between buildings. And they were durable – many of the concrete elements are virtually impossible to destroy, even though concrete construction was only meant to be a temporary solution for the next 30-40 years. But the vast majority are still standing, and over time the facades have been painted, central heating has been installed, the buildings have been thermally insulated and the old electrical installations renovated. All in all, many have become decent homes, even if you can still hear your neighbour going to the toilet or quarrels in the apartment downstairs. But you can also do that even in very modern apartment blocks.

The apartments were often clustered in small residential areas that resembled a provincial town. There were shops, libraries, medical centres and other everyday necessities.

Minimum-sized flats, one next to the other. But you live right in the city centre. There are plenty of them around Warsaw. Here Grzybowska Street 16/22

Many of the new residential areas sprang up just outside the city, but as an example close to the centre, I’ve chosen Grzybowska 16/22 – Here you’ll find cosiness, climate and small restaurants – and a 15th floor apartment block from 1972. If you walk into the centre of the building, you can walk unobstructed into the entrance hall, where you’ll notice the constant traffic of residents coming and going. The 420 flats are clustered in long corridors and many of them are around 30 square metres in size. It may not be a particularly appealing building, but residents are close to EVERYTHING.

Plenty of lifts to get you up and down quickly

Lazienkowska Road – a big road in the middle of the city

(Trasa Łazienkowska)

The post-war period was also a time to rethink new transport systems. Cities were devastated, there was room to change the road layout and expand existing road networks.

Across almost all of Poland (and also in some Western European countries), wide main roads were established that cut through neighbourhoods. In Poland, pedestrians could cross the street via high footbridges, which were not tempting if you had poor fitness or walking difficulties. Instead of bridges, pedestrian tunnels were sometimes built where young people often hung out and where timid citizens were reluctant to go.

Huge roads cutting through city centres, intersecting and separating neighbourhoods from each other, were part of urban planning in Poland after World War 2. However, similar trends could also be seen in some Western countries.

As a result, neighbourhoods were separated from each other and to this day, the Old Town in Gdansk, for example, has remained a separate island from the rest of the city. In Warsaw, however, car tunnels were chosen for certain stretches, such as the East-West route at Castle Square or the Łazienkowska route in the image below from Plac na Rozdrożu (300 metres from the Politechnika Metro). However, these huge accumulations of traffic through the city centres still created a segmentation of the city.

Ministry of Finance or maybe MiniPlenty

Address ul. Świętokrzyska 122. A stone’s throw from Metro Nowy Świat Uniwersytet.

I tend to think of Orwell and call it MiniPlenty when I pass by this palatial 1956 building that provides for the Polish economy.

Ministry of Finance – looks even bigger in real life than in this picture. Inside, dark and conspiratorial. Here was the real power in Poland for long periods after World War II and the change of system, when the economy was a top priority.

The building is basically constructed in a modernist style, taking into account the requirements of real socialism for modern architecture. However, you can also find plenty of Renaissance and Baroque in the building.

The interior design is obviously elegant and expensive, a far cry from what you would expect from a modern and efficient workplace. You get the distinct impression that this is the real centre of the Polish state, a time warp that no ideology or crisis will be able to blow away.

Warszawa Wschodnia – Eastern railway station

Address ul. Kijowska 20, but also access from ul. Lubelska. Approx. 10 minutes from Metro Stadion Narodowe.

Warsaw has three major railway stations – Centralna in the centre of the city, the Western Railway Station, which is currently being modernised and completely renovated, and the Eastern Railway Station, where you can still revel in the communist architecture.

Eastern Railway Station

The railway station was originally built in 1866, but was destroyed during World War II. The new station was completed in 1969 and was considered a monumental example of modernist railway construction with its interesting geometric shapes. However, cheap solutions were used during construction and the railway station quickly fell into disrepair. Partially renovated in 2012.

Office building under communism – Intraco I

Address ul. Stawki 2. Ten minutes walk from Metro Dworzec Gdański.

In early 1970, an order was issued from party headquarters that all of Poland was to be modernised. This included modern office skyscrapers in all major Polish cities. Many of them were horrible examples of eyesores with miserable indoor climates, but the Warsaw office block was the prestige building, designed for foreign companies. With 107 metres to the roof and 39 floors, the modernist building was completed in 1975.

Modern Poland – under communism

Originally, the entire building was covered with a mirror facade, but after a renovation in 1998, the building is now covered with ceramic tiles. The other high-rise buildings around Poland from the same period have also all been either facade renovated or demolished.

Russian Embassy

Address: Belwederska 49. A stone’s throw from the Belweder Presidential Residence and the Ministry of Defence. Bus 116 from Castle Square or on public holidays from Plac Trzech Krzyży.

The former Soviet embassy was built by imported construction workers and with building materials from the Soviet Union. It’s beautiful, huge and reminiscent of a king’s palace. Along with the Palace of Culture, it was one of the buildings that established Russia’s dominant role in Poland with solid bricks.

The proximity of one of the most important Polish representative buildings, the Belweder – today the presidential residence – is also striking, and when the ambassador needed to speak with Polish-Russian Defence Minister Rokossowski (Polish Defence Minister 1949-1956, Soviet Deputy Defence Minister 1958-1962), he only had to walk through a door in the wall separating the embassy from the Ministry of Defence.

The north of Ursynów

Ursynów metro. Simply walk around the area. A 20-minute stroll will give you a good impression of the neighbourhood.

In 1970, Poland was still hungry for housing for its people after the devastation of the war, and the economic climate was favourable for foreign borrowing and housing construction. An architectural competition was organised to see who could best transform 220 hectares into a vibrant residential area.

Plans for the area date back to before World War 2. Like many other places in the world, they were inspired by the ruler city, so that cities did not expand in all directions, but rather like fingers on a hand. Today, this stretch is complete centred along Aleja Komisji Edukacji Narodowej (National Education Commission), where the metro line also runs.

Main street to Warsaw city centre and metro line

Ursynów was one of the neighbourhoods that expanded the most in the 1970s, with huge amounts of concrete blocks being built, making it one of the capital’s major suburbs. These were fields and meadows where urban planners had already decided to build a city 10 years earlier. It is also the last major centrally planned urban expansion of the period, and it is done in accordance with the building norms of the time and the building materials that were available in Poland at the time – with concrete slabs being the dominant building material.

Small local squares and centres were built so that residents basically didn’t have to leave their local area

You can think what you like about concrete blocks, but they solved an acute housing shortage for many people, and they also managed to create a unity where the buildings with their diversity gave the area a certain life. In addition to the apartment blocks themselves, a large number of parks and landscape areas were created, and the surplus soil from the building process was often laid out to construct a hillside landscape between the apartment blocks, where children can play and sledge in the winter.

In the beginning, it was still a bit rural. That’s changed, but there’s still plenty of space, green areas and opportunities to play.

However, it took many years to complete, so under communism, Ursynów was a somewhat abandoned area that had never been completed. However, the 1990s saw the arrival of the metro, the completion of express roads, new architecturally exciting construction projects, and shopping centres, schools and sports facilities that helped turn the area into an independent entity. And above all, whether by car or public transport, it’s extremely fast to get to the city centre.

The missing link – the transition between late modernism and real socialism

62 Wspólna Street, 82 Marszałkowska Street (corner of Wspólna Street)

The period after Poland’s independence in 1918 opened up a fantastic belief in the future. Poland was invincible, the future belonged to Poland. This was also reflected in architecture, with impressive and functional buildings springing up all over the country. Concrete was predominantly used and the structures were well thought out, without being troubled by unnecessary elements.

But they were modern to the technology that existed at the beginning of the century.

We find examples of interwar modernism all around Warsaw and Poland, but the most blatant example is in Gdynia, which was built as a harbour city by government decree and was one of the hottest things imaginable at the time.

62 Wspólna Street, 82 Marszałkowska Street (corner of Wspólna Street)

The period after Poland’s independence in 1918 opened up a fantastic belief in the future. Poland was invincible, the future belonged to Poland. This was also reflected in architecture, with impressive and functional buildings springing up all over the country. Concrete was predominantly used and the structures were well thought out, without being troubled by unnecessary elements.

But they were modern to the technology that existed at the beginning of the century.

We find examples of interwar modernism all around Warsaw and Poland, but the most blatant example is in Gdynia, which was built as a harbour city by government decree and was one of the hottest things imaginable at the time.

After World War II, Stalin reformulated the architectural vision and the Polish communist leader Bierut was personally deeply involved in its implementation in Poland. Real socialism inherited many of the elements of modernism, but also drew inspiration from classicism and antiquity. The new buildings were characterised by columns, monuments and reliefs – the working class should feel that these were their buildings, they were the ones who were now princes – even if the buildings were usually filled with bureaucrats. The new socialist architecture had to be national in form and socialist in content. This meant that Polish elements were constantly emphasised in the new buildings, which were also meant to create a sense of national identity.

However, before that – just after the end of World War II – there was a transitional phase where the architects were well aware of which way the winds were blowing, but the doctrines were not yet clearly formulated. During this period, Polish architect Marek Leykam was responsible for the construction of a number of buildings, primarily on Wspólna Street, so if you’re visiting the Ministry of Agriculture, it would almost be a shame not to include these late modernist buildings from the beginning of the communist era.

Ufficio Primo

(62 Wspólna Street) is inspired by the Italian Renaissance. The building was intended to be the headquarters of the government, but only fulfilled this role for a few months. However, the circular interior exudes power and the two underground floors bear witness to a time when the world could have been facing a new war. The lower basement region is designed as a nuclear shelter, which could be home to 400 top Polish executives if necessary. From 1993-2008, it was home to an exclusive music club where U2, among others, played.

I usually take all the photos in this guide myself, which is the reason for the low image quality. But here I have borrowed an image from Wikimedia, which shows the dome, among other things.

Created by Emptywords – Praca własna, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=120414465

The building itself has an identical ornamented facade on all sides, while the roof is in the form of a dome that lets light into the circular hall indoors. Today, the building belongs to a large Polish listed company, which uses it as its headquarters.

Outside, the entrance is flanked by Greek and Roman gods, which were installed in 2015 by the building’s current owner.

Squaring the circle is resolved with stairs in the corners. Light comes from above and spot lighting, and the flooring makes the columned halls reflective. The upper columned halls are inspired by the Wawel Royal Castle in Krakow, and below are two more floors that are identically designed – the lower one with nuclear protection. I visited the building, but with a strict photo ban, so I’m borrowing this from Wikipedia:

Autorstwa Kgbo – Praca własna, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=82752740

Wspólna 56 – Marek Leykam

The office building next to Ufficio Primo was also designed by Marek Leykam and, together with Marszałkowska 82, helped create a small late modernist enclave in Warsaw. Today, the building is used as an educational centre.

Wspólna 56 – part of Marek Leykam’s late modernist vision immediately after WW2.

Marszałkowska 82 – Warsaw City Court

– which I call the Thousand-Door Kingdom, is home to the District Court of Warsaw City Centre. A more classic name for the building, however, is ‘The Razor Blade’ (Żyletkowiec), which refers to the shape of the windows. Also completed in 1952, this building was located in the middle of what was then the vision of the centre of power in the city, right next to the later Ministry of Agriculture.

The building was originally intended for the Ministry of Mining, but was later taken over by the National Audit Office before being handed over to the judiciary in 2005.

Warsaw City Court for the Centre of Warsaw

Please send an email to m@hardenfelt.pl if you would like an English-speaking tour guide to show you the most important places in Warsaw.