Jewish Warsaw

#Warsaw tour guide #Warsaw city guide # guided tour in warsaw #Warszawa tour guide #Warszawa city guide #guided tour in Warszawa

400,000 Jews in Warsaw before WWII

The Jewish community in Warsaw made up around a third of the population at the outbreak of World War II. With 400,000 Jewish residents, it was the second largest Jewish community in the world after New York. Many lived as normal Polish citizens who didn’t identify much with Judaism. Many children didn’t even realise they were Jewish. But there was also a certain antipathy towards Jews among the Polish population and integration was difficult. Many Poles did not consider it possible for a Jew to become a Pole and also treated Jews living as Poles as an alien element.

Warsaw was as Jewish as Polish before World War II

Almost all Jews in Warsaw spoke Polish, but many had Yiddish or other languages as their mother tongue. Jews had lived in Poland for generations, and through the Middle Ages it was natural for each community to have its own norms and rules. This was maintained well into the 20th century, although many tried to integrate.

Jews were forced to wear yellow Stars of David from September 1939

With the German occupation of Warsaw at the end of September 1939, Jews were forced to identify themselves by wearing Jewish stars on their arms, and relatively quickly the Jewish population was gathered in a closed ghetto. During the war, Jews were largely eliminated from Warsaw, and the few remaining Jews were to some extent pressed to leave Poland after the end of the war.

Most of the remnants of the Jewish culture has been destroyed

Most of Warsaw was destroyed, some was preserved and much was rebuilt to commemorate the Jewish presence in Warsaw – a city that, as previously suggested, was as Jewish as it was Polish.

A tour around Jewish Warsaw is a specialised knowledge that some people spend a lifetime sublimizing. With that in mind, the suggestions below may seem superficial, but I’m trying to be practical and pragmatic. As a foreign visitor, you only get a superficial view of this complicated history. My recommendations include:

POLIN – the museum of the history of the Jews in Poland

POLIN is much more than a history of suffering

– Museum of the History of the Jewish People, address ul. Anielewicza 6. Metro Ratusz Arsenal. About 400 metres from the metro. If I personally had to pick just one museum in Warsaw that I would recommend, this would be it. Even if you don’t want to go inside the museum, take a look at the building and the monument outside.

Opened in 2014, the museum is located right in the centre of what was the Jewish ghetto during the Nazi occupation

Jews have been in Poland for almost a thousand years

The exhibition is very detailed, but it allows you to choose what you are most interested in. If you opt for a guided tour (English), you may be so overwhelmed with information that the atmosphere is lost. The history of the Jews is not just the exterminations during World War 2, but a thousand years of presence in Poland, where the Jews grew together with the Polish state, although they retained their uniqueness.

Entrance hall shaped like an inverted ark

Delicious kosher food at the restaurant

There is a weapons check with metal detectors before entering the museum, but you can enter the lobby without buying a ticket. You can also enjoy original and delicious kosher food at the restaurant (self-service).

Jewish Warsaw – 2 hours walk with a guide. Price: 350 zloty

Jews have been in Poland for 1,000 years, but of course, World War II is particularly important here. I’ll tell you about both the war and what happened before and after. Please click at the headline to continue.

Nożyków Synagogue

– (Synagoga im. Małżonków Nożyków). Address Ulica Twarda 6. About 400 metres from Świętokrzyska Metro. 10-12 minute stroll from the Palace of Culture.

Until the outbreak of World War II, Warsaw was the Jewish centre of Europe with around 440 synagogues. Today, there are six active synagogues in Warsaw, with Nożyków Synagogue being the only major one.

Nożyków Synagogue in Warsaw

The synagogue was damaged during WWII

The building dates from 1902 and was severely damaged during World War 2. For a period of time, it served as one of the few open synagogues in the Jewish ghetto.

The synagogue is open to visitors Monday to Friday and admission costs 10 zlotys. Men should bring a head covering, but skullcaps are also available to borrow.

The Jewish Theatre – Yiddish Cultural Centre

Address Senatorska 35. 5 minutes from Metro Ratusz-Arsenal.

Theatre performances in Polish and Yiddish (with translation into Polish with headphones). One of only two theatres in Europe that regularly perform plays in Yiddish.

The Jewish Theatre – next to Plac Bankowy and Saski Garden in the centre of Warsaw.

The Jewish cemetery

– Cmentarz żydowski. Address ul. Okopowa 49/51. Next to the Powązkowski Cemetery. Approx. 10 minutes walk from Ratusz Arsenał Metro or from the Museum of Jewish History POLIN. Admission to the cemetery costs 10 zlotys.

200,000 headstones

Headgear is mandatory

A sign outside requires men to wear headgear, while you have to remember to remove your headgear if you enter a Catholic church. That’s how complicated it can be when you try to assimilate a little culture.

Dating from 1806, the cemetery is divided into sections and contains 200,000 headstones, making it the second largest Jewish cemetery in Poland after Lodz. It is the clearest testimony to the huge Jewish community that lived in Warsaw before World War II.

The cemetery is still active, but with the small Jewish population in the city, no more than an average of one funeral a month is held.

The ghetto in Warsaw (big and small).

City centre.

The wall around the ghetto was built gradually from April 1940 – initially with barbed wire, later with bricks. Within a short time, the ghetto was completely sealed off and any exchange of goods or entry and exit was controlled.

The official food rations were totally inadequate for survival, so the vast majority of food entering the ghetto was smuggled in. Those who had money or valuables could sell them and survive a little longer. Incidentally, smuggling was punishable by death. However, smuggling did not prevent hunger.

The shape of the ghetto can be seen on boards throughout the old ghetto area

The ghetto constantly changes shape and size

The size of the ghetto changed as needed, so it’s not possible to give a fixed size, but in 1941, around 450,000 people lived in around 3.5 square kilometres. The ghetto was also divided into the Large and Small Ghetto, which were connected by a footbridge. The wall surrounding the ghetto has long since been demolished, but in many places it is marked by a line in the pavement and in many places a model of the ghetto stands next to the old wall.

The road to the extermination camp

The ghetto was gradually liquidated by sending the residents to extermination camps. Gradually, the residents realised that they were not going to labour camps, but were being systematically murdered. This prompted a small group of remaining Jews to revolt against the Germans in 1943, an uprising that lasted from 19 April to 15 May. After the rebellion was put down, the entire ghetto was systematically demolished, leaving nothing but rubble on the ground. The intention was that a German neighbourhood would eventually be built here.

In the film “The Pianist” we see how society functions during the occupation

Life in the ghetto has been depicted in numerous films, but one of my favourite international feature films is Polanski’s ‘The Pianist’, which vividly depicts the struggle for survival, while the residents still retained the ability to keep society going and maintain a certain cultural life. Polanski experienced the Krakow ghetto as a child, but has based his film about the Warsaw ghetto on historical facts.

The bridge between the big and small ghetto

Corner between Żelażna 68 and Chłodna. Approx. 15 minutes walk from both Metro Arsenał and Metro Rondo ONZ.

An artistic installation from 2011, reminiscent of the old wooden bridge that separated the Large and Small Ghetto. This was an important tram line, so the Germans chose this solution to keep the tram network functional.

Photographer unknown. Public domain.

Four pillars and a light installation symbolise the original bridge. On the pavement are slides that allow you to view original photos from the ghetto.

Installation where the original bridge stood, with slides and commemorative plaques

Across the street is the Red Pig restaurant – great atmosphere with a parody of the communist era and good food in the same style – But with slow service, especially if you’re in a larger group.

Fragments of the wall at Zlota street

Sienna 55/ Złota 62. A few minutes from Metro Rondo ONZ.

The wall can also be seen from Jan Paweł II Street between the side streets of Sienna and Złota, The wall is in a schoolyard, so you have to look over the railings and plantings to see what’s happening

18 kilometres long and 3 metres tall

The 18 km long wall around the ghetto was 3 metres high and was further reinforced by one metre of barbed wire. The wall is long gone, but a small piece has survived here in the backyard, which is an interesting tour in itself. A few commemorative plaques tell the story of the wall and the ghetto, while a few bricks have been removed and sent to Jewish museums. As it’s a residential area and there are many visitors, the use of loudspeakers is prohibited and visitors are encouraged to speak softly if they need to converse.

The backyard – a little difficult to find, but there are signs. It’s a good idea to be reasonably quiet as the flats next to the wall are normally occupied with residents.

You go through a gate to get into the backyard, so it’s not necessarily easy to find, but look for signs and you’ll find your way

Jewish tour of Warsaw

600 zloty for 4 hours by car and walking. The most important Jewish memorials in the city and the history of Jews plus World War II. Please click at the headline to continue.

Monument to the Heroes of the Warsaw Ghetto

(Pomnik Bohaterów Getta). Zamenhof Street – right in front of the main entrance to POLIN. Under 10 minutes walk from Metro Ratusz Arsenal.

The current monument was erected in 1948 – right here in the centre of the Jewish ghetto that had been razed to the ground. It consists of a large stone (basalt) on a plinth, which has bronze reliefs engraved on both sides.

One relief is called “Fight” (Walka), referring to the fighting during the 1943 ghetto uprising, where men hold bottles of petrol and grenades in their hands, while a young woman holds a child.

Fight – with your back to the museum

The other side is called “March to Extermination” (Pochód na zagładę), showing Jews on their way to the extermination camp and the German helmets.

Willy Brandt Kneeling in Warsaw

In 1970, Willy Brandt suddenly knelt down outside protocol in front of the Monument to the Heroes of the Warsaw Ghetto. It was a gesture that had great symbolic significance as an acknowledgement of German guilt.

Anielewicza bunker and the Jewish cemetery on Muranów

Miła Street on the corner of Dubois Street. A few hundred metres from the POLIN Museum. 10-12 minutes walk from Metro Dworzec Gdański or Metro Ratusz Arsenal.

In the no longer existing bunker, Jewish combat units were hiding for extended periods during the war. The bunker was attacked by the Germans in May 1943, killing around 120 people, some of whom committed collective suicide, while a few survived and made it to the Aryan side of Warsaw.

The pre-war address was Miła 18, which is immortalised in Leon Uris’ novel Mila 18 about life in the Warsaw Ghetto during WW2.

The site has not been excavated and is thus labelled a mass grave.

Umschlagplatz Monument

Address Stawki 10. 8-10 minutes walk from Metro Dworzec Gdański. 4-5 minutes from POLIN.

During the war, this was the site of the ramp for the railway tracks that in 1942-1943 sent Jews from the ghetto to the Treblinka extermination camp.

The monument was erected in 1988 and consists of large stones symbolising an open railway carriage, which was often used for transport to the camps. Inside the “railway carriage” are engraved the 400 most popular Jewish and Polish names from before World War 2. A plaque in Polish, English, Yiddish and Hebrew commemorates the 300,000 people who were sent from here.

Umschlagplatz – a station on the road to the extermination camp

Grzybowski Square

(Plac Grzybowski). A few hundred metres from Metro Rondo ONZ, around 10 minutes’ walk from Metro Świętokrzyska. A stone’s throw from the Synagogue.

Plac Grzybowski – a large and vibrant square with cult status

For centuries, this was the site of one of the satellite towns whose fate was linked to Warsaw until it was incorporated into the city of Warsaw in 1795. During the 19th century, the square was developed with splendid classical residential buildings, and in 1861 the Church of All Saints (Kościół Wszystkich Świętych) was built, designed by the famous classicist architect Henryk Marconi. It’s a huge church that – although not a typical tourist attraction – is well worth a look, both inside and outside. During the ghetto period, it served as a church for Christian Jews.

Around 1900, the area around the square was predominantly inhabited by Jews, who, among other things offered processed metal goods.

As mentioned, the boundaries of the ghetto were constantly changing, and from 1942 Plac Grzybowski came under the Aryan side of Warsaw and was inhabited by Poles. This saved the square from total destruction after the 1943 Ghetto Uprising. However, the buildings were generally damaged by the war and the 1944 uprising. In particular, the neighbouring Próżna Street (ul. Próżna) survived the German destruction. It has until recently been in ruins, but is in the process of being restored to its former glory. Overall, Próżna Street is a good street if you want to get an impression of pre-war Warsaw.

Próżna Street – The only street in the ghetto that was not levelled in 1943

Until recently, the entire square was in a state of disrepair, but in the last ten years, complete renovations have restored the residential buildings to their former glory, and the square and its neighbouring side streets are now one of the city’s meeting places. A number of restaurants have opened, some of which are upmarket.

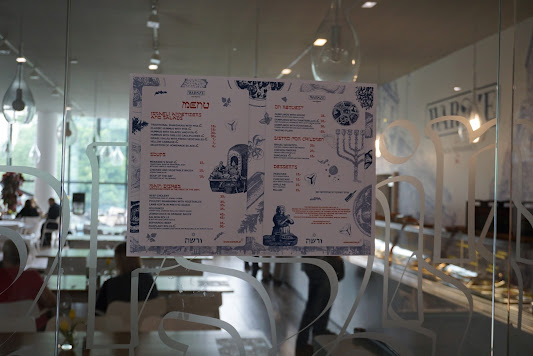

There are also a few Jewish restaurants in the area around the square, including Kosher Delight (Grzybowska 2) and Koszerna kuchnia (Twarda 6).

The Jewish Cemetery – Targówek

Cmentarz Żydowski (Targówek). ul. św. Wincentego 15. 10-15 minutes walk from Metro Targówek.

The walk from Metro Targówek to the cemetery takes you through an interesting mix of newly built apartment blocks, concrete blocks from the 1970s and lower buildings from the 1950s.

Some people claim that Warsaw is not Poland, just another international city. But if you take the metro from metro Świętokrzyska, 12-13 minutes later you’ll be at Metro Targówek mieszkaniowe. When you step out, the dynamism is replaced by provincial idyll, workshops with unusual specialisations and a relaxed atmosphere. In short, we are in Poland.

Around a quarter of a million people are buried in this oldest Jewish cemetery in Warsaw, dating back to 1780. The cemetery was last used in 1940 and is now overgrown and destroyed. Some of the stones were used in the rebuilding of Warsaw, but today efforts are being made to restore parts of the cemetery

The entrance to the cemetery. You usually have to ring the bell to be let in

Ring the bell to enter (Monday-Thursday 10-16, Friday 10-14). The clerk will give you a brief explanation of the cemetery and will also appreciate it if you buy a ticket for 10 zlotys to visit the adjacent museum, which tells the history of the cemetery in Polish and English with accompanying photographs.

The vegetation is allowed to grow wild

Tombstones from unknown graves collected in steel cages

Please send an email to m@hardenfelt.pl if you would like an English-speaking tour guide to show you the most important places in Warsaw.