Polish language

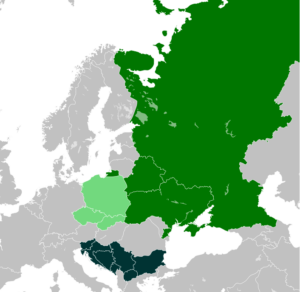

Language group

Polish is a Slavic language. This means that Polish is related to Russian, Bulgarian and Ukrainian, among others. The closest related languages are Czech and even more so Slovak, which can be understood across languages if people are talking about a topic they both know or if they’ve had a glass of wine. I have personally travelled around the Czech Republic speaking Polish and even if there are communication problems, you manage to explain the things you need.

Ukrainian is a little further away, and it can be difficult for a Ukrainian to achieve a pronunciation that doesn’t give away that you’re from the east. But… the grammatical structure is roughly the same and many words are identical. If you drop a Ukrainian into Poland with a parachute, they’ll be able to explain themselves and shop at the nearby supermarket.

Russian is not immediately understandable, but some older Poles have had Russian at school. But not everyone learnt it, as many were not very happy to learn Russian, which was considered the language of the oppressor. Plus, it’s been over 30 years since Russian was universally taught in schools, so if you haven’t used it since, it can be difficult to remember.

If you come from the Slavic language area or have already learnt Russian, learning Polish will be relatively easy. The structure of the language is roughly the same and the grammar is built on the same basic principles. However, there is considerable variation in pronunciation.

The common features of the Slavic languages are:

- A multi-case system where the endings of nouns, adjectives and pronouns change depending on the case used.

- Division into masculine, feminine and neuter gender

- Two different verbs cover the same meaning, with the difference being that one is “done” and the other is “unfinished”.

Ophavsret: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Slavic_europe.svg

Light green = Countries where a West Slavic language is the national language

Dark green = Countries where an East Slavic language is the national language

Dark blue = Countries where a South Slavic language is the national language

Poland has had plenty of contact with neighbouring nations over the years and words have been borrowed between the languages, especially from German, although etymologically the word ‘German’ (niemiec) means ‘the mute’ or ‘non-speaker’. Much of it comes from the Middle Ages, when Germans often arrived as settlers, both as farmers or as craftsmen and traders in the cities. But that’s not enough to understand each other. On the other hand, Polish has a large number of loanwords from Latin that have seeped into other European languages. From English and American, on the other hand, there is a strong modern influence, both in informal language and specialised language in different branches.

All this means that if you have a Polish written text, a Western European will be able to guess a lot of words, especially if they speak a few foreign languages. If you also learn the 1000 most common Polish words, you’ll be able to quickly deduce what a written text is about.

All this means that if you have a Polish written text, a Western European will be able to guess a lot of words, especially if they speak a few foreign languages. If you also learn the 1000 most common Polish words, you’ll be able to quickly deduce what a written text is about.

On the other hand, for most Western Europeans it will take a long time before they understand spoken Polish, and even longer before they start speaking it, although … there are 7-8 words that most people learn very quickly and that you can actually get a long way with:

kurwa – a swear word that also means whore. Used as an exclamation mark, dash and amplifying prefix. You don’t have to use the word yourself, but it’s good to know it..

Piwo – beer

Rozumiem – I understand

Nie rozumiem – I don’t understand

Dziękuję (udtales: dzienkuje) – thank you

Ile – how much

Tak – yes

Nie – no

There are two main problems with understanding spoken Polish. Firstly, people usually speak quickly and secondly, the sounds are often unintelligible to most people from Western Europe or America. In principle, Polish is phonetic, meaning it is pronounced exactly as it is spelled, which is a result of language centralisation after World War I – there are simply very few dialect differences in Polish. But to enjoy this connection between written and spoken language (which we don’t have in English or Danish), you have to delve deep into the sound system.

If you haven’t learnt Russian or another Slavic language beforehand, a Western European will also face an almost insurmountable wall when it comes to conjugating Polish words. Nouns, adjectives and pronouns are conjugated in gender, number and 7 different cases, while verbs (in addition to tense) are conjugated in gender and according to the person, which isn’t so bad if you speak a Romance language. Furthermore, among verbs, there is a contrast of performed and not performed in the form of two different words that are usually created by a prefix or another variant of the base word. You may be able to learn these new concepts with concentrated effort, but it’s not easy to automatise them in your language use.

Polish is the official language in Poland – that means street signs are in Polish and any communication from the government is in Polish. The same is true for teaching in schools.

With around 38 million Polish inhabitants and a few million emigrants and descendants of emigrants/displaced persons who speak Polish on a daily basis, it is estimated that around 42 million (maybe slightly more) have Polish as their primary language. There are various estimates, but it would be safe to place Poland among the top 40 most spoken languages in the world.

Dialects and minorities

If you discuss dialects with a Pole, they’ll often claim that Poland has dialect differences too. The main dialects here are Mazowiecki, Malopolski and Wielkopolski. It’s about some sounds being voiced and unvoiced and certain other differences in pronunciation. A few regional words can also be found. But firstly, it’s all relatively mixed, and secondly, the differences are so small that even well-educated Poles are not able to easily identify where other Poles come from based on these dialects. For example, while Danish, English, German, Dutch, French and Spanish have distinct dialect differences that are obvious to everyone, this is far from the case in Poland. This is probably due to a centralised language policy initiated after the First World War, and also to the fact that after the Second World War, Poles were shuffled like a pack of cards.

Obviously a few regional words can also be found. In Wroclaw, the language is still characterised by a few words from the former eastern Poland because the citizens of Wroclaw are mostly descendants of people who were displaced from the now Ukrainian city of Lwow during the post-war border changes. In Warsaw, you can also find some reminiscences of an urban dialect of Praga, perhaps because the neighbourhood was “liberated” early on by the Red Army, and thus not affected by the destructions of 1944-1945.

Udført af: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Polska-dialekty.png

Kashubian is spoken daily by around 100,000 people north and west of Gdansk. It is defined as a regional language, and in some municipalities proceedings are bilingual (Polish and Kashubian) in contact with citizens. In areas where Kashubian is spoken, it can be taught in schools at the request of parents, but the general education is conducted in Polish.

Some people believe that Kashubian is a dialect, but the question of dialect or independent language is often influenced by political views. Nationalist groups see Poland’s unity and indivisibility as fundamental to its survival and are enraged at any moves towards regionalism.

Although Kashubian grammar is virtually identical to Polish grammar, a Pole will not understand two people having a conversation in Kashubian. However, all Kashubs speak Polish and can switch from Kazzubian to Polish at any time.

There have been attempts to recognise Silesia as an official minority, but this has been blocked by the Polish President, who fears regionalism in Poland. Silesian is more of a dialect than a language in its own right and is easily understood by Polish speakers, although they sometimes smile when they hear Silesian on TV.

Around 500,000 people around Opole and Katowice speak Silesian, which is characterised by German loanwords.

– some Poles live in Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania. These people speak a slightly old-fashioned Polish that is instantly recognisable to people who speak standard Polish.

People in the mountains in the area around Krakow have some interesting folk costumes, sing folk songs and do folk dancing, so they are often put into one of the old costumes and displayed on the market square in Krakow and other tourist towns.

They speak a language where the vocabulary is characterised by their life in the mountains, and they also have loanwords from Czech and Slovakian. They are also characterised by having lived in isolation from the changes elsewhere in Poland. All this adds up to a language that sounds funny to most Poles, and you’re unlikely to get a good job if you only speak in your native language. But… it is part of tradition and diversity in Poland.

The vast majority of Germans were expelled from Poland after WW2. After World War II, a small group was allowed to stay, especially around Opole (it was explained that they were Poles who had been Germanised). Ethnic Germans currently number around 150,000; they have the right to run their own bilingual schools, and in areas where ethnic Germans live, children are offered 3 hours of mother tongue lessons per week.

The importance of gender

As in most European languages, nouns are divided into masculine, feminine and neuter gender, and this is not just a grammatical division. Poles more or less consciously gender-identify all objects and actions. Most job titles clearly point to a man or a woman, and part of the women’s movement is fighting for female forms for leadership positions, such as director, minister or supervisor, and it’s a battle they are winning. However, many women also choose to use the male form as it seems more serious. In some places there is a difference in the content of the position; the female form of secretary will for example brew coffee, answer phone calls and file documents, while the male form (even if female) will usually have management responsibilities. Adjectives and pronouns also have genders and align with the gender of the noun.

There are exceptions to the following, but masculine words usually end in a consonant (syn, komputer, telefon), feminine words in -a (kobieta, ulica) and neuter words in -o, -e, -ę or -um (auto, morze, cielę, muzeum).

Verbs in the past tense are also divided into gender; singular into masculine, feminine and neuter, while plural is divided into male humans and other. Male humans should be understood to mean that if the verb refers to a single male person, the form for male humans is used. When referring to women, animals, gloves or cigars, the form for “other” is used. While foreigners may be forgiven for not having learnt the gender of the noun or making mistakes in the conjugation pattern, if they refer to the wrong gender when using a verbal form, they are simply considered unintelligent or rude. The constant emphasis on gender can be confusing and frustrating for a Dane or Englishman who normally thinks in neutral, unisex terms, but has also been brought up with equal treatment and strict gender neutrality.

Orthography

Polish maintains a number of special characters, but generally the characters consist of the basic Latin alphabet. Furthermore, historical development has meant that some of the letters represent identical sounds. There have been calls for a revision of Polish orthography for many years, but so far the traditionalists have had the upper hand.

There are strict rules for the spelling of different words, and zero spelling mistakes is a basic condition for being taken seriously. One of the most serious offences a Pole can commit is using the letter ‘ó’ instead of ‘u’ or vice versa. These two letters are pronounced as the exact same u-sound, but not choosing the right letter would classify the writer as uneducated in the eyes of many language puritans. Some of them will think it would be better not to write anything at all. It should be noted that a large part of school time is spent practising the correct use of these two letters as well as the letter pair rz/ ż, where exactly the same problem applies.

Once you’ve learnt the sounds of the alphabet, Polish written language is surprisingly straight forward. You can generally pronounce a word you’ve seen in writing and you can easily write words correctly even if you don’t know them. But of course, you need to have learnt both the alphabet and the sound system first.

The specific Polish letters – supplementing the Latin alphabet – are:

ą – ch – cz – ć – dz – dź – dż – ę – ł – ń – ó – rz – sz – ś – ż – ź

The letters q, v and x are only used in loanwords and only to a very limited extent.¨

Pronunciation

Polish is generally pronounced differently than Western European languages. In fact, there are so many differences that most English speakers, who briefly consider learning Polish, run away screaming when they become acquainted with the sounds; or perhaps they never become acquainted with the sounds, and this may actually be the problem.

The ability to understand and reproduce sounds is usually learnt as a child or teenager and can be difficult later in life. You can always find an exception, so of course there are particularly musical people who are able to capture the contrasts, even though they’re getting older. The result, however, is that most Western Europeans pronounce Polish with sounds from their own language. The worst result comes if you buy a Polish textbook and start learning the words based on how they are written in the book. It’s not just a matter of having a weird accent; the words and inflections have a cohesion that is connected to the sounds, and you simply don’t get a natural relationship with the language without having learnt the sound system. This makes it difficult to remember the words and endings.

In my opinion, if you want to learn Polish, you should start with the sound system, also because this is the key to the grammar, which largely follows the framework of pronunciation. IT WOULD BE A GREAT IDEA TO GET PROFESSIONAL HELP TO TRAIN THE SOUNDS.

Both vowels and consonants are generally pronounced slightly differently than in Western European languages. The differences are marginal, but when you pronounce whole words, the differences become apparent. The most difficult, however, are the special Polish sounds that are equipped with special letters or are formed from compound letters.

ch – pronounced like Polish “h”

ó – pronounced like Polish “u”

rz – pronounced like “ż” (see below)

“ą” and “ę” – Nasal vowels. Pronounced as “on/ oun” and “en/ eun”. However, in some compounds, they are not pronounced nasally, in which case they are pronounced as a regular Polish “a” or “e”. This is especially true for ę when it’s at the end of a word.

ł – a bit of a w sound

ć, ń, ś, ź – are called soft vowels. Basically pronounced as ci, ni, si, zi

cz – a bit like “ch” in “chip”, but the sound needs to be trained

dz – a bit like “dj”, but the sound needs to be trained

dź – a bit like “dji”, but the sound needs to be trained

sz – a hissing sound. Must be trained.

ż – like “sz”, but tuned

dż – like “cz”, but tuned

You practice the sounds by practising the correct mouth and tongue position and then pronouncing sounds that are close together. These letters are:

sz, ż, cz, dż – all four sounds are formed by holding the tip of the tongue upwards. Sz and ż create friction, cz and dż create an explosion. The sounds sz and cz are unvoiced, ż and dż are voiced. With voicing, there are some fluctuations in the sound, but if you don’t understand the principle of voicing/unvoicing, it’s something that needs to be trained with a teacher.

si, zi, ci, dzi – For these four sounds, the tongue is straight out or slightly upwards. Si and zi are long, ci and dzi are short. Zi and dzi are voiced, si and ci unvoiced.

s, z, c, dz – The tip of the tongue is pointing downwards. Sz and ż create friction, cz and dż create an explosion. The sounds s and c are unvoiced, z and dz are voiced. You can read more about the Polish sounds and hear examples at https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Polish/Polish_pronunciation

Nouns

As mentioned, Polish nouns are divided into 3 genders. These 3 genders take either singular or plural forms, and are also conjugated in 7 different cases. Each gender has a number of regular case inflections that depend on the ending of the noun. In addition, there are a number of exceptions. Pronouns and adjectives are also conjugated in case.

There are exceptions to the following, but masculine words usually end in a consonant (syn, komputer, telefon), feminine words in -a (kobieta, ulica) and neuter words in -o, -e, -ę or -um (auto, morze, cielę, muzeum).

The case system

It’s a little easier to understand the case system if you’ve had Latin, but even a solid grasp of German grammar can go a long way. If you only speak English, the case system initially seems like a daunting obstacle, and it can be hard to realise how a language can benefit from a case system.

To put it simply, in English we have fixed rules for word order:

Per hits Jan – the subject is first in the sentence. It is the one who takes an active action, in this case “Per”. Then comes the verb (hits), and finally the direct object, the one who is the object of the action (Jan). If we reverse the sentence so that it reads: Jan hits Per, then it’s Per who gets a bloody nose.

Word order rules are looser in Polish, instead you have cases. Piotr beats Jan is rendered in Polish with: Piotr bije Jana. Piotr is in mianownik, which is the form the root takes. Jana is biernik, which is the form the object takes.

Below are the Polish cases and their primary functions. Please note that this section is only meant to give an idea of the structure of the Polish language. This is not an exhaustive list.

– the base form. The subject is in the nominative case.

– many functions, but the three most important are 1. If the subject is negated, it is in dopełniacz (He has a lot of money – in this sentence “a lot of money” is the subject and in biernik/ he doesn’t have a lot of money – in this sentence “a lot of money” is in dopełniacz because it is negated with the word “not”. 2. Genitive – like ‘s form in English: The gardeners dog = Pies ogrodnika (ogrodnika = the gardener’s, and is in genitive, just like in English). 3. A number of prepositions form a prepositional phrase with dopełniacz, you can also talk about the prepositions controlling dopełniacz.

– 1. The direct object is in biernik (unless it’s in a negative form, in which case it’s in dopełniacz). 2. A number of prepositions form a prepositional phrase with biernik. Often the same preposition has a choice between two different cases, and the choice is often about whether the action is static or dynamic.

– 1. The Instrumental form is the instrument used to perform an action and is most often placed in narzędnik. 2. In Polish, the subject complement (when there is an identity coincidence between the subject and object) is in narzędnik, for example: Peter is a painter (painter is in narzędnik).

– only used in prepositional phrases. These are primarily static prepositional phrases that indicate a place where someone/something is located.

– expresses indirect object, but note that Polish sentence analysis is different from English. It may be better to consider see celownik as the recipient of the direct object or to who the direct object is given. Furthermore, a number of prepositions take celownik.

– a form of address. Mrs Kowalska, how happy I am to see you! Here, Mrs Kowalska is put in wołacz because it is a form of address. The use of wołacz is on the decline; mianownik is often used instead. As a foreigner, you can take this form lightly.

Each verb has a built-in sentence structure. So when learning a verb, you don’t just need to know what it means, but what structures exist. If we look at the verb “to hit”, all Poles will know a number of example sentences. They know that we use the standard phrase “mianownik + slå + biernik”. If we want to expand the sentence, we have the schema: Someone (active) (mianownik) + hit + someone (passive) + with something (narzędnik):

Per hit Jan with his fists = Piotr bije Jana pięściami

In principle, you can manage with migrant Polish with the first three cases and then practice the rest over the years.

Verbs

Polish verbs have three tenses; present, past and future. In addition, a distinction is made between telling about something (indicative) and giving orders (imperative). There is also a hypothetical (subjunctive) form, which is formed by adding the suffix -by.

Active and passive. As in English, the vast majority of sentences are in active. An active Polish sentence can be changed to passive, where the subject of an active sentence becomes a passive element of a passive sentence.

Peter eats an apple (active) >The apple is eaten (by Peter) (passive).

The average English speaker shouldn’t have any major problems with verbs.

Polish verbs are conjugated in person, just like in Spanish or Latin. In Polish, personal pronouns (I, you, he, she, it, it, we, I, they) are usually not necessary because they are built into the verb ending. The endings are learnt through repetition and is not the same for all verbs. They are divided into inflectional groups and there are also a lot of irregular verbs.

In the singular past tense, verbs are also conjugated in gender (both in 1st, 2nd and 3rd person). Using the right gender is seen as important in Poland. The past tense plural distinguishes between male and non-male persons (women, animals and objects). If only a single male person is included in the subject, the form for male persons should be used.

Aspect is a form, that may present problems for English speakers. Polish verbs are divided into dokonany (done) and nie-dokonany (not done). Dokonany has a past and future tense (but no present tense). Niedokonany has past, present and future tenses. Dokonany and niedokonany can be two very different words, but are usually forms that are close to each other. Most often, dokonany is formed by adding a prefix to a niedokonany verb.

Diminutives

Poles love diminutives and derivatives that gives affection to a word or name. Diminutive forms are formed using endings. Almost all Polish first names have one or more diminutive forms. These forms are used by family, friends and often work colleagues. Girlfriends and boyfriends often like to give each other diminutive animal names, frequently calling each other little fish, little frog, little cat or (for men) bear and little bear. When you wait for money you expect to get some “small money” and your car will often be a “small car”

Swear words

By far the most popular Polish swear word is “kurwa”, which literally means “whore”, but is used as a swear word in the sense of: gee, damn, fuck, etc. The word is used frequently in Polish, but is considered rather vulgar. People who consider themselves to be well educated will often use “kurczę” (chicken) or “kurka wodna” (small water hen) instead of “kurwa”. Swear words most frequently refers to sexual acts or genitalia and is often borrowed from Russian or English, with “fuck” being a favourite among the younger generation.

Familiar form and respectful form

Polish maintains two forms of address. “Ty” (you) is used among family and friends, but increasingly among work colleagues, and young people will often say “ty” to each other without thinking about it.

The respectful form Pan (hr.)/ Pani (Mrs) is used with elderly people and where you want to maintain a distance, for example in shops and public offices. Furthermore, the form is used where there is a hierarchical difference. It’s rare for a boss to be on friendly terms with his employees, and at universities it’s absolutely the norm to refer to your teachers/students as Pan/Pani. However, the familiar form is slowly but surely spreading, so there may be variations in formality depending on where you are.

Language law

In recent years, legislators have become concerned about the Polish language; in 1996, a Polish Language Board was established to protect the language, and in 1999 a Polish Language Act was passed, even though the language has actually survived for hundreds of years without having s much as a Polish state.

In addition to the law stating that the Polish state must support the spread of the Polish language, it also determines that regulations and public institutions in Poland operate in Polish. Polish is also the language to be used in trade, invoices and contracts in Poland, as long as one of the contracting parties is Polish. As a foreigner, you cannot sign an English-language rental contract with a Pole (although the Polish version can of course be translated into English).

How to learn Polish

As I mentioned earlier, for a English speaker, learning Polish is significantly more difficult than learning Western European languages (German, Spanish, French, etc.), and the difficulties clearly increase with age. It’s important to realise what your goal is. If you want to be able to shop in the local shops, just try to learn a few words and phrases and don’t worry too much about how correct they are. If you want to be able to understand the essentials of written texts, it’s not that difficult. Learn the most common 1,000-2,000 words and then be good at guessing. You shouldn’t worry about grammar.

The difficulty comes when you want to speak a varied and correct Polish. You can’t do this without knowing the sound system well, and once you have learnt this, vocabulary and grammar will come much easier. There is a big difference in how quickly people are able to assimilate the sound system. Age is one determining factor, musicality another.

I would personally recommend some one-to-one lessons (10 – 60 depending on musicality and level of ambition) with a speech therapist before you start learning Polish, or possibly alongside it. A speech therapist is called a “logopeda” in Polish and can be found in most medium and large Polish cities. Most Polish teachers will think they know enough about the subject to teach, but their knowledge is often very theoretical and they don’t usually have the pedagogical tools and patience that speech therapists have.

One method is to buy a book and ask your partner or friend to help you learn the language. You can try it, but it’s difficult to teach Polish and will rarely give good results. However, self-study and the help of friends can go a long way once you’ve spent a few months learning the sound system.

You should realise that you can’t translate word for word and expect to make up a Polish sentence. Polish is different in structure compared to Western European languages and the best way, in my opinion, is to learn whole sentences and then replace individual words.

If you choose private lessons, find a Pole with a degree in Polish and preferably one that specialises in teaching Polish to foreigners.

Furthermore, many private schools have sprung up offering Polish for foreigners, and here too the quality is varied. You should try to obtain materials from the schools you are interested in, talk to them and assess their seriousness, and possibly try your hand.

If we’re talking about teaching materials, it’s important to realise that Polish has never been number one on the list of languages that foreigners wanted to learn. This is slowly changing, but it means that excellent teaching systems have not been developed as in English, German, French or Spanish.

Today, an abundance of schools teaching Polish to foreigners has sprung up. I don’t have an overview of the individual schools/universities, but if you’re in Warsaw, I recommend the University Polish for Foreigners, where the teachers are definitely well-qualified and there is a wide group of students from all over the world. Click on the logo to go to the website

When choosing a school/university/private tutor you should also be aware of:

- Experience! Teaching Polish to people from Western Europe is not easy. Languages are fundamentally different and if you’re not aware of the learner’s background, teachers will often consider language structures to be obvious, even if the learner finds them incomprehensible.

- Who participate in the course Some schools (especially full-time one-semester courses) get their students primarily from descendants of Polish emigrants. These are people who may not speak Polish, but have heard Polish in their childhood and usually have no problems understanding the grammar or pronouncing the sounds. It can be suicidal to join such a ‘beginners’ group’. Furthermore, groups can be filled with participants from Ukraine or other Slavic countries who quickly learn basic Polish. Also this will also be demotivating for a Western European. Ask about the participants before you start a course.

In my opinion, some of the best materials currently available are the series Hurra (1,2 and 3) from the publisher Prolog. They have also published some grammars in English and German as well as the textbook Start 1, labelled as survival Polish with English explanations. Click on the logo to go to the website!

The Universitas publishing house from Krakow publishes the biggest amount of books for teaching Polish to foreigners. They offer a wide range of books from beginner level to C2. There has been a revolution in teaching materials in recent years, so look for books published in recent years. Some of the older books are very theoretical and lack a pedagogical approach. Click on the logo to go to the website!

Many, many years ago, the publishing house Wiedza Powszechna published a book called Uczymy się polskiego (We learn Polish). The book is published in editions with different help languages (English, German, Italian, etc.), and audio and grammar can be added to the system. Although modernised, it’s a bit old-fashioned and probably best if you are primarily looking to learn to READ Polish, but it is well done and in my opinion useful for self-study. Click on the picture to go to the website!

Please send an email to m@hardenfelt.pl if you would like a English-speaking tour guide to show you the most important places in Warsaw.